3 Foundations

Final draft.

Note: sections about Jang Il-soon and the Wonju Group draw heavily on the author’s own translations of material from the Biography of Jang Il-soon by Kim, Sam-Woong: The Beautiful Life of Muwidang.1

The foundations of Hansalim reach into the history of the anti-colonial and anti-dictatorship struggles that shaped Korean culture through the twentieth century. Although cooperative practices had existed in Korea from ancient times, modern western cooperativism was brought to the peninsula during the 1920s when Korea was a colony of Japan. From that time, cooperatives played a key role in the independence movement until the sino-Japanese war. Then throughout the struggle for democracy during the 1960s - 80s cooperatives supported the growing resistence against the dictatorships of Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan. Finally, when democratisation began in 1987, the way was opened for the full flourishing of cooperative enterprise. In this chapter we will trace the history of Korean cooperativism from its colonial era roots to the beginning of democratisation through the story of four of Hansalim’s founders who I am calling the Artist, the Bishop, the Teacher and the Poet.

3.1 Origins of Korean cooperativism

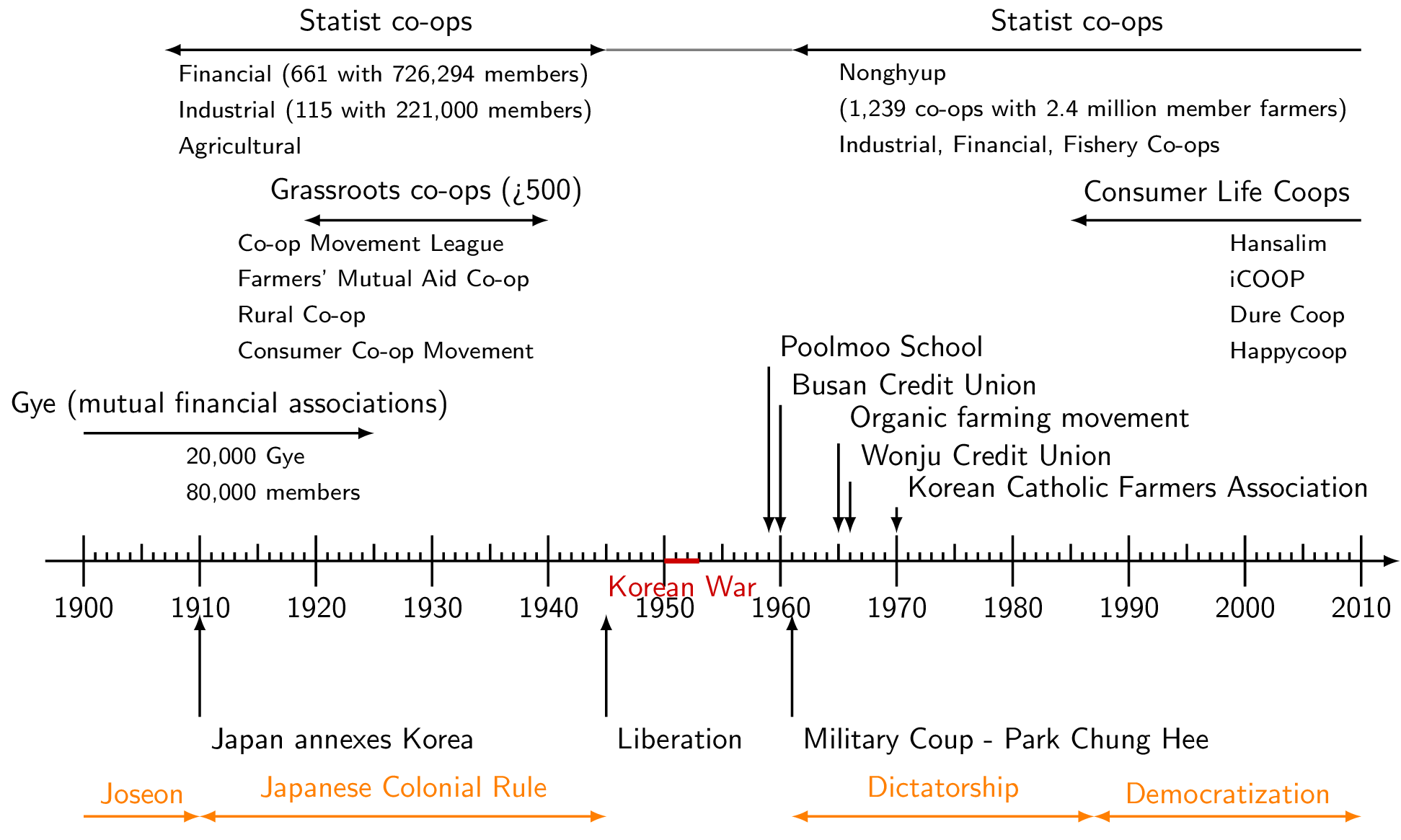

The annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910 was the culmination of a long history of invasions and exploitation of the peninsula. It solidified Japan’s control over Korea and began a long period of oppression during which many of the freedoms of Korean citizens were restricted and the colonial government embarked on a project to destroy Korean cultural, linguistic, and national identity and to completely assimilate Korea through a wholesale re-education of the population through economic domination and their own colonial school system.2 As part of this project, the colonial government also developed a national infrastructure of state-run agricultural and financial cooperatives to manage rural and industrial development and facilitate top-down control and decision making.3 The Korean resistance against the colonial government sought to apply alternative models of cooperativism inspired by grassroots movements from Europe and Japan as well as Korean traditional models of autonomous mutual self-help that had been already present in Korea since the precolonial era. These included reciprocal resource sharing associations called Gye,4 cooperative labour associations called Dure,5 mechanisms for voluntarily assisting those in need in the local community called Pumasi6 and the tradition of Kimjang, the communal making and sharing of Kimchi.

Thus, under Japanese colonial rule, cooperatives in Korea evolved along two parallel pathways – statist and grassroots (see Figure 3.1). While statist cooperatives appeared to contradict the very principles of cooperativism – being extensions of the state bureaucracy and neither independent nor democratic – grassroots cooperatives developed in connection with Korean nationalist and socialist movements dedicated to Korean independence.7

While statist cooperatives appeared to contradict the very principles of cooperativism - being extensions of the state bureaucracy and neither independent nor democratic - grassroots cooperatives developed in connection with Korean nationalist and socialist movements dedicated to Korean independence.8 Many solidarity-based cooperatives in finance, farming and education were established independently of the Act of the Japanese Government-General of Korea and promoted nationwide under the guise of informal voluntary organisations outside the colonial government’s formal oversight.9

In the 1920s, 180 production and consumption associations were created that brought together participants from a diversity of social strata, including housewives, female students, workers, farmers, students, intellectuals. The numbers of these cooperatives doubled every year from 1926, reaching at least 500 by 1938, and the number of participants (members) was at least 140,000. However, since 1932, the number of cooperatives established nationwide gradually decreased as large-scale cooperatives linked to labour unions and farmers’ movements were suppressed by the colonial government.10

After the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, most cooperatives were forcibly converted into rural promotion movements or dissolved due to the mobilisation for war and their leaders were arrested.11 Nevertheless, some independent schools persisted in promoting democratic and cooperative ideas. At one such school was a young teenager called Jang Il-soon.

3.2 The Wonju Group

3.2.1 The Artist

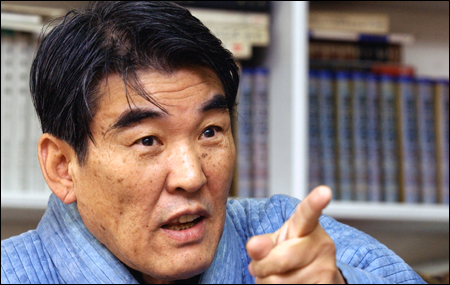

Jang Il-soon was born in the city of Wonju, just south of Seoul, in 1928 while Korea was a colony of Japan. He was baptised a Catholic in 1940 at the age of 12 and attended a high school in Seoul founded by an American Methodist missionary back in 1885. It was an independent school where he was taught Korean history and about the fight for Korean independence. The school had a printing facility and encouraged students to publish school journals and organise cooperative associations. This was his first experience with cooperatives. Upon the liberation of Korea in 1945, Jang Il-soon was 17 and in his second year at Seoul National University, the most prestigious in the country. In 1950 he transferred to study philosophy but his studies were cut short by the outbreak of the Korean war.

After the war, instead of continuing his studies, he returned to his home town of Wonju which had suffered terrebly during the war as the site of many fierce battles. There he opened a school to provide education to children in Wonju whose lives had been so devestated by the war. Supported by his family, he taught at the school without taking a salary and provided the schooling free of charge.

By the age of 30, Jang Il-soon had become a well known figure in the resistance against the military dictatorship that had taken over from the United States before the Korean war. When Park Chung-hee took power in a military coup in 1961, Jang Il-soon was immediately arrested as an alleged communist sympathiser. Along with hundreds of other pro-democracy activists, Jang Il-soon was tried as a criminal against the state. His sentence was 8 years in prison. In all he spent 3 years imprisoned while his wife and two young children waited for his release. During this time, his wife, Lee In-sook, supplied him with books to read on all subjects from the classics of Western and Eastern literature to contemporary works of progressive social thought. He used this time as a period of reflection and education which prepared him for the new task that would eventually become his life’s work.

After his release from prison he was still not really free, however. The Park regime placed him under constant surveillance and even tried to stop people visiting him at his house so that the safest place to meet people was at church on a Sunday. This surveillance lasted so long that it continued under the next dictatorship of Chun Doo-hwan. In 1981 the government even built a police station at the end of his street to monitor who came and went from his house.

Eventually, harassment by the intelligence services forced him to give up teaching. So he took up farming grapes and painting calligraphy (hence why I call him ‘The Artist’). As a farmer he noticed how other farmers were using pesticides sold to them by Nonghyup and getting sick and poisoning the land. He realised that his land was not only inherited from his ancestors, but also borrowed from his descendants so he farmed it organically without using any agricultural chemicals. Little did he know then, that his life was about to change when he met the new Bishop of Wonju, Ji Hak-soon.

3.2.2 The Bishop

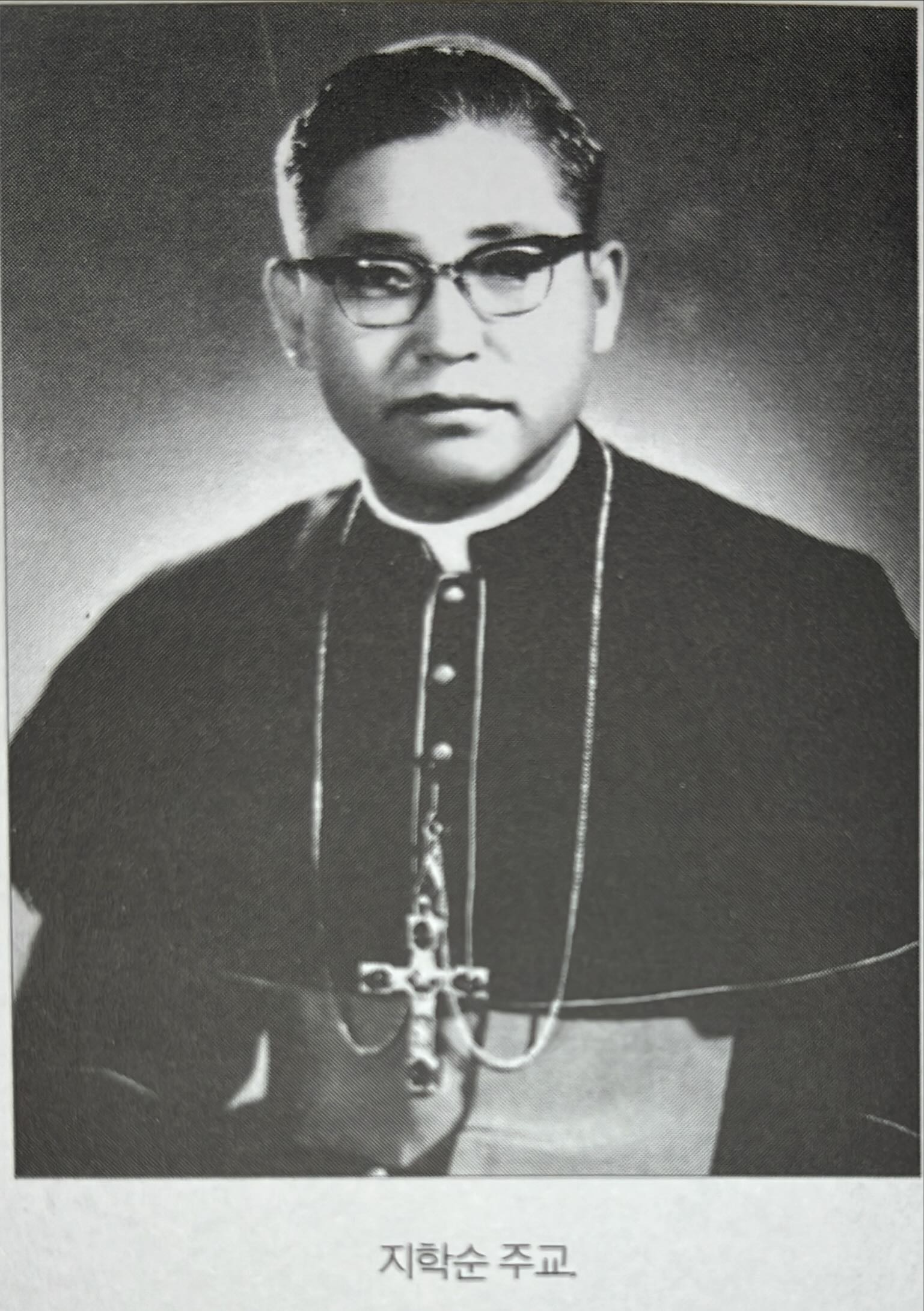

In 1965 the Pope appointed a young priest, Ji Hak-soon as Wonju’s first bishop. He had left North Korea before the war to train as priest in Rome and, while there, he was deeply impacted by the spirit of the Vatican Two Council which urged the church to become more outward focused on the needs of local communities and to support ecumenical unity; to become a church run by and for the people, and for the poor and marginalised in particular.12 It was in Wonju, that Ji Hak-soon met Jang Il-soon who was to become one of his closest friends. Within the context of the church, the Bishop gave Jang Il-soon the opportunity to teach again and, in 1967, he began training lay Catholic members to prepare for a transformation of the church into a self-reliant lay-centred organisation that supported a wider rural development movement of credit unions and cooperatives.13

With a population of just 100,000, Wonju diocese was an impoverished region of coal-mining and farming communities. The church was dependent upon foreign aid for its survival and the town itself was a cultural backwater with very few resources. As soon as Ji Hak-soon took office he and Jang Il-soon set up Wonju’s first credit union in 1966 and founded Jinkwang Middle School in 1967. Jang Il-soon began to organise training courses for cooperative and credit union members and established the Cooperative Education Institute in Jinkwang school to develop the cooperative movement beyond the Catholic Church. The school’s students and teachers also created the first school cooperative in Korea, Jinkwang Cooperative, to purchase books and equipment and run the canteen. One of the teachers at the school was Park Jae-il.

3.2.3 The Teacher

In 1969, after his release from prison for his involvement in pro-democracy protests, Park Jae-il moved to Wonju to join the Social Development Committee and the Catholic Farmers’ Association, led by Bishop Ji Hak-soon. He became a teacher at Jinkwang School and attended on of Jang Il-soon’s lectures after school one day. He was so captivated by the vision for reviving cooperation among the common people that he quit teaching to join the cooperative movement full time, taking up a key role in the Cooperative Education Institute. From that moment he became a lifelong student of Jang Il-soon and worked alongside him and Bishop Ji Hak-soon in the cooperative and rural development movement in Wonju. He would later become the president of the Catholic Farmer’s Association and then Hansalim’s first Chair of Directors.

In addition to promoting education Bishop Ji Hak-soon also built cultural spaces, hospitals and welfare facilities for the disabled. Among these projects, the most significant was the cultural centre which he built in front of Wonju Cathedral. Sponsored by religious organisations from Europe and the United States and dedicated on July 12th 1968, the Wonju Catholic Center was the first civic cultural centre of the Korean Catholic Church. The three story building – run by the diocese and staffed by young lay church members – included offices, meeting rooms, an exhibition hall, projection room, first-floor cafeteria, basement room and dormitories. It quickly became a popular meeting place for young people and a hive of creative activity, hosting performances by local musicians and exhibitions by local artists. The main hall was used to stage plays by Wonju’s Sanya Theatre Company directed by Jang Il-soon’s younger brother Jang Sang-soon and the basement room was the venue for DJs to play pop and classical music from a record collection which apparently exceeded even that of the local radio station!

Around the Bishop (Ji Hak-soon), the Artist (Jang Il-soon), and the Teacher (Park Jae-il), an informal network of pro-democracy and cooperative movement activists began to gather. The Wonju Group, as they were known, began to expand the cooperative movement beyond Wonju into Gangwon province and to forge links across religious and ideological divides. Both Jang Il-soon and Ji Hak-soon made a point of reaching out beyond the boundaries of the Catholic church to other religious groups, not only to other Christian dominations but also to Buddhists. Priests, pastors and monks would visit each others congregations to preach and meet regularly at restaurants to share meals and talk together. The Catholic Church in Wonju became a church not only for believers but for all people striving to build a better and more democratic society. Following the example of Jesus, they sought to serve those in need without distinction and to freely support all who worked for the good of the whole community.14

Jang Il-soon saw the cooperative movement as a training ground for democracy for the whole community and a means of empowering people to become responsible citizens.15 He described it as a “movement for service to the masses, abandoning arrogance and radical elite consciousness.” and a “downward crawling movement.”16 In his lectures, Jang Il-soon reminded people of their own traditional culture of rural cooperation in Korea through Dure (farmers coops), Gye (village credit unions) and Pumasi (informal labour exchange). He referenced the 19th century history of cooperation among the British working class (the Rochdale Pioneers) and the credit union movements in France and Germany as examples of people finding ways to break free from corporate exploitation and live together on their own terms through mutual aid and self-reliance.17 He drew inspiration not only from Jesus’s teachings but also from Buddhist scriptures, Daoist and Confucian philosophy, Korean traditional spirituality and Ghandi’s example of non-violent resistance to enlarge people’s awareness of themselves and the world.

As a symbol of this broad and inclusive vision, the Wonju Catholic Centre became a hub for students and other pro-democracy activists and writers who gathered from Wonju and beyond to talk and drink late into the evenings in the cosy basement room. One of those young people was a poet named Kim Young-il who wrote under the pen name “Ji-ha” (芝河).

3.2.4 The Poet

Originally from Mokpo, Kim Ji-ha had moved as a child to Wonju with his parents. At Seoul National University he became active within the pro-democracy movement in Seoul and, when he returned to Wonju, he brought with him a cast of activists and artists who quickly joined forces with the growing cultural movement (minjung movement) in Wonju. Together they created yard plays (a form of traditional peasant theatre called madang-geuk, 마당극), mask-dances and plays for theatre. These plays raised the profile of Wonju among the wider national minjung movement and before long, Wonju was being called the holy land of the pro-democracy movement.18

Together, with the Wonju Group, Jang Il-soon and Ji Hak-soon reorganised the church in the Wonju diocese into a network of self-governing self-supporting parishes and set up a program of education and training aimed at empowering the poor and marginalised to form self-sufficient self-governing communities across Gangwon province. Their vision was for a cooperative movement that was economically and politically independent from the authoritarian state and which promoted rural and urban development led by communities themselves. However, just as things were starting to take off catastrophe hit.

3.2.5 The Great Flood

In 1972 the large-scale flooding of the Namhan River basin caused widespread devastation in Gangwon and surrounding provinces. In Wonju Diocese the floods damaged 50,000 buildings and displaced more than 140,000 people.19 Bishop Ji Hak-soon went to Germany to ask for funds from the catholic charities Miserere and Caritas to support rebuilding. With the money they provided (2.91 million marks or around $360,000 today) he set up a Disaster Countermeasures Project Committee to coordinate a long-term recovery project. However, instead of simply providing unconditional aid, as was normally done under such circumstances, the committee targeted their resources at supporting communities to become self-sufficient. Food and money were given as wages for productive work rebuilding communities, restoring farmland and developing new income sources for farmers.

Young people from the Wonju Diocesan Youth Association who had been involved with the cooperative movement in Wonju were recruited to act as counsellors. Their role was to visit the affected villages, learn about their needs and provide advice and training to enable villagers to take leadership of the reconstruction and development process themselves. This was a particularly special time for Jang Il-soon. He began to see what he had been dreaming of for so many years take shape in reality in his own community. Hundreds of villages across three provinces participated, creating credit unions and cooperatives, restoring the culture of shared agricultural labour and managing their affairs democratically through village assemblies. Others saw what was happening too and the pattern of rural development through cooperation that began in Wonju spread across the country.

Although these efforts made a significant and lasting contribution to rural development and democratisation20, they were carried out in resistance against the increasingly authoritarian Yusin regime under Park Chung-hee. Top-down state-led projects of agricultural industrialisation, rural improvement and political indoctrination through Nonghyup and the Saemaul Movement (New Village Movement) contributed to the ongoing suppression of the Wonju group’s activities. In a bid to achieve self-sufficiency in rice, the state adopted a new high yielding rice variety, Tongil rice, which was rapidly extended to farmers through a combination of incentives and coercion.21 It required heavy fertiliser and pesticide application to achieve its promised yields22 which were supplied exclusively through Nonghyup. These pesticides were highly toxic and little training was provided to farmers about how to minimise risk of exposure. Despite the undeniable improvement in rural incomes stimulated by the state-led green revolution, as the use of chemical pesticides rapidly increased through the 1970s many farmers became sick from pesticide poisoning, ecosystems became increasingly polluted and food safety concerns grew among consumers. Jang Il-soon and others in the Wonju Group began to recognise the dangers of too narrow a focus on productivity and profit sharing. Somehow, cooperation needed to be extended beyond humans to include the natural world in a symbiotic relationship.

3.3 Set-backs

3.3.1 Under attack

Then, in 1974, in what seemed like retaliation against the Wonju Group, Bishop Ji Hak-soon and poet Kim Ji-ha were arrested, along with 253 others. Ji Hak-soon faced a court martial under new emergency measures brought in by Park in reaction to growing unrest and pro-democracy protests among university students nationwide. His sentence was 15 years in prison on the charge of funding an anti-state group and masterminding a plot to overthrow the government. Kim Ji-ha was sentenced to death, commuted to life and released after 10 months only to be arrested again and his death sentence renewed. He spent 7 years in prison until he received a stay of execution.

Under pressure from the newly mobilised Catholic resistance and widespread anti-government protests, Park released Ji Hak-soon in 1975. But the government’s suppression of democratic movements intensified with new emergency measures and sweeping powers to control anyone who opposed him. During this difficult time, unable to engage directly in pro-democracy activism or the cooperative movement Jang Il-soon painted calligraphy, drew illustrations and wrote poetry, holding exhibitions to raise funds in support of others and communicate his resistance through art. In the years up to 1979 unrest and mass protests continued to spread until the shocking assassination of General Park by his own head of Central Intelligence, Kim Jae-gyu. The democracy movement, that had been suppressed by Park, sprang back to life, as people rekindled hope for a transition to genuine democracy. But the new government fell in a matter of weeks as the chief of defence General Chun Doo-hwan led a military insurrection on December 12th 1979 and soon declared martial law.

3.3.2 The Seoul Spring and the Gwangju Massacre

The immediate reaction by citizens has become known as the “Seoul Spring”. Waves of mass protests spread across the country as students and workers took to the streets to oppose the military’s takeover and call for democracy. The military’s brutal response involved mass arrests, beatings, torture and killing of protesters. Things quickly came to a head in the city of Gwangju in south Jeolla province, a hotbed of pro-democracy activism.

While mass protests in the city had been held peacefully with police cooperation during the previous days, in preparation for General Chun’s final takeover of the government, paratroops and tanks had been sent to Gwangju to suppress the protests, beginning by arresting most of the leaders of Gwangju’s democracy movement. On May 18th, when students attempted to enter the city’s Chonnam National University campus they were brutally beaten by the waiting paratroopers and turned away from the university gates. This provoked spontaneous protests among students which spread across the city throughout the day, calling for an end to martial law and the removal of Chun Doo-hwan. This time, they were met by violence from the riot police and confrontations escalated throughout the day as students fought back and the numbers of protesters steadily grew. When the paratroopers began to chase down and to strip and beat the demonstrators and bystanders alike, the student protest became a popular revolt.23

The next day it wasn’t just hundreds of students on the streets but around four thousand citizens - high school students, shop owners, labourers, housewives, priests and teachers - came out to support the students and confront the police and paratroopers in front of Province Hall. When the police fired tear gas and the paratroopers charged the demonstrators, they responded by breaking up paving stones to throw and collected metal pipes and other implements to use as makeshift weapons. Molotov cocktails, drums of oil and nearby vehicles were used to attack and drive back the troops. Taxi drivers took on the role of ambulances to take the injured protesters to hospitals. Buses, trucks and phone booths became barricades.24

The clashes between citizens and military became more violent and the paratroopers used their batons, rifle buts and bayonets to attack the crowds and hunted people down as they fled down alleys and into nearby buildings. Whoever they captured they stripped, beat and tortured, leaving many dead or with life changing injuries and taking many more students back to their camp as prisoners. Even some of the riot police who tried to help the wounded, unaccustomed to the extreme violence perpetrated by the military forces, were themselves attacked by the paratroopers.25

Over the next few days more than 200,000 demonstrators fought against the police and paratroopers across the city. Convoys of over 100 taxis and some buses and trucks joined the demonstrators on the streets and some began to use vehicles as battering rams and fire bombs to attack the paratroopers blockades. The streets were covered in burning cars, debris and the bodies of dead and injured protesters lying in pools of blood. Citizen Militia began to capture vehicles, explosives, rifles and ammunition to strengthen their stand against government forces who had begun to use live ammunition on the crowds leading to several fatalities and provoking growing rage among the citizens. Then the paratroopers deployed machine guns, automatic rifles and snipers to attack the citizens and military helicopters also opened fire on the crowds. Despite their resort to lethal force, the paratroopers were overwhelmed by the scale of the uprising, and withdrew to the outskirts of the city where they prepared for a large-scale offensive with reinforcements from the army’s 20th Division.26

The demonstrators took control of Province Hall and other parts of the city center and organised a Citizen Settlement Committee to negotiate with the government forces. Having withdrawn from the city centre, soldiers blockaded Gwangju and were ordered to use lethal force against any resistance. Finally, after five days of blockade, in the middle of the night on the 27th May 1980 three special forces teams and a division of more than 3,000 soldiers moved on the city centre to recapture Province Hall and Gwangju Park in a battle that ended with 27 citizens and 2 soldiers dead and 295 citizens detained.27

Over the course of the uprising, 20,000 trained soldiers were deployed to the city of 800,000. The total number of casualties is not known, as the government acted quickly to cover up the incident and manipulate the data reported. Conservative estimates are that over 200 of Gwangju’s residents were killed by government forces and many more hundreds injured while the so-called ‘ring leaders’ were imprisoned and tortured. Despite the immediate government cover up, news of the massacre at Gwangju spread among democracy activists and students and helped to undermine the legitimacy of the Chun regime, becoming a rallying cry for the pro-democracy movement.28

3.4 New directions

The events in Gwangju were followed by rumours that the government was preparing to target other cities like Wonju which were also centres of pro-democracy activism. Deeply shocked and grieved by the news of Gwangju, and fearing for the people of his own city, Jang Il-soon went into hiding and urged everyone to keep quiet. His lack of action angered many in the democratisation movement and marked the beginning of a shift in his attitude towards forms of political resistance.

3.4.1 Inspiration from Donghak

A few months after the Gwangju uprising and subsequent massacre, Kim Ji-ha was released from prison in December 1980. A lot had happened since his initial arrest and he had also had time to reflect himself on the experience of the Wonju Group. When he was reunited with Jang Il-soon they discovered they had both come to the same change of direction in their thinking.

Jang Il-soon described it in this way:

“The Hansalim movement was something I had been thinking about for decades, and another was the consumer cooperative movement in the 70s (260), and as I continued the anti-dictatorship movement, I realized that I had to break out of the old Marxist paradigm, because it was not going to solve the problem, and it was going to continue the vicious circle. When I saw that they were spraying pesticides and fertilizers and trying to industrialize the city, I thought that the entire riverbed would be devastated. I told Mr. Park Jae-il, who was trying to start a rural movement in Wonju after the June 3 incident,”We should go in the direction of saving the farmland and food for the community.””29

Since the mid-1970s, Jang Il-soon had been developing his philosophy and way of life around the teachings of Haewol (Choi Si-hyung), a virtually forgotten leader of an indigenous Korean religion called Donghak (sometimes written Tonghak and now known as Cheondogyo or the Heavenly Way). It was the ethical and cosmic vision of Donghak, and especially the practical spirituality of Haewol which became the foundation of the Hansalim movement as it emerged in Wonju through the 1980s.

Donghak was founded in 1860 by Su-un (Choi Je-u)30 at a time when Korean society was in turmoil under pressure from foreign interference, rapid economic change, a corrupt bureaucracy and a monarchy in the process of collapse.31 Su-un taught that all things bear Hanullim (divine life) within themselves and that ‘sagehood’ or unity with Hanullim was open to all regardless of education, class, gender or age simply through sincerely seeking and stilling ones own heart to listen. His message of equality, simple spirituality and reverence for the sacredness of all things, spread like wildfire among the peasantry and disillusioned middle classes alike. Fearing a revolution, the authorities quickly arrested him and executed him in 1864.

Su-un’s successor, Haewol expressed the Donghak teaching that ‘people are heaven’ in three practical rules: honour heaven (敬天), honour people (敬人), and honour all things (敬物). These three phrases express the idea of serving people as heaven and valuing the life of all natural things equally. Jang Il-soon revived Haewol’s teachings and sought, through Hansalim and the Life Movement, to implement them in the form a new kind of cooperative movement that unified humanity with one another and the cosmos in a symbiotic and spiritual relationship. He is quoted as saying:

“Hae-wol, the second teacher of Donghak, said that if you know a bowl of rice, you know everything in the world, and Byeong-hee, Ui-am Son, also said that a bowl of rice is”born of a hundred people” (百夫所生), that is, it is made by the sweat of many peasants. He said that, but isn’t it true that it’s not just people who make it by sweating, but the heavens, the earth, and the whole world become an ensemble and move together as one, so that bowl of rice becomes a cosmic encounter? “If you go a step further, there is a saying in Haewol’s words, ‘Ichun-sikcheon’ (以天食天), which means that heaven eats heaven. In Donghak, it is called ‘innaecheon’ (people are heaven, 人乃天), and not only people are heaven, but every grain is heaven, every stone is heaven, every worm is heaven.”32

Haewol’s three ‘noble truths’ (三敬说) – honour heaven (경천, 敬天), honour people (경인, 敬人), and honour things (경물, 敬物) – formed the core of Jang Il-soon’s philosophy and provided him with a language through which to synthesise ideas from Christian and Donghak thought. At the first training session for Hansalim activists in 1991, Jang Il-soon explained:

“Here, ‘honour heaven’ (gyeong-cheon, 경천) does not refer to the sky as we commonly understand it, but rather to our own minds, the true mind within our hearts, not the thoughts that come and go, but the innate true mind. Christians might refer to this as God the Father. Next, ‘honour people’ (gyeong-in, 경인) means serving all people. Then, ‘honour things’ (gyeong-mul, 경물) means serving all things in the universe.

Just a few days ago, we celebrated Easter, but during Holy Week, Pilate said to Jesus, ‘You say you are a king, don’t you?’, ‘You call me a king, don’t you?’ [Jesus replied]. This is a very important statement. ‘You call me a king, don’t you?’ ‘What kind of kingdom is yours?’ ‘The kingdom you speak of is not the same as mine.’ Isn’t that what he meant? This is also a very important message in our Hansalim movement. When I say that your kingdom is different from mine, I mean that my kingdom is the kingdom of life. The kingdom of life. All things coexist, all people coexist, and therefore all people are kings. What kind of kings? The sons of God the Father are kings. The daughters of God the Father are kings. This is what it means. If God the Father does not exist, if the source of life does not exist, then we do not exist.”33

Jang Il-soon’s words reveal his rejection of religious dogma and political ideology in favour of a generous openness which is reminiscent of Bishop Ji Hak-soon’s own approach in Wonju during the 1970s. The issue at stake for Jang Il-soon is not one of belief but of attention, attitude and act. He asks his listeners not only to attend to heaven, but also to oneself, to others and to all things with an attitude of reverence which is expressed in the act of service.

This new direction was sharply at odds with the rest of the democratisation movement at the time which was becoming more explicitly revolutionary and militant in response to Chun Doo-hwan’s intensification of violent suppression. By 1985, it was clear that the memory of the Gwangju uprising and the Chun government’s massacre of civilians was firmly fixed in the national psyche and each year following, the anniversary of the uprising was marked by increasing numbers of participants who commemorated the victim’s sacrifice for democracy. Students began to resort to to self-immolation and public suicide as new forms of protest. Jang Il-soon was horrified by this self-destructive violence in protest against the regime and called instead for non-violent, passive resistance instead of violent struggle.

The new emphasis on the natural world as sacred and a spirituality that looked suspiciously more like shamanism or Buddhism than Catholicism must have been hard to accept for many of the devout Catholic members of the movement. It might seem odd then, that a movement led by Catholics and grounded in the Catholic church should come to embrace an apparently non-Christian philosophy. But on closer inspection, Donghak actually seems quite well placed to fit alongside Catholic social teaching by re-emphasising the sacredness of the nonhuman world. Jang Il-soon’s reinterpretation of Donghak ideas within his own life as a Catholic and his ability to bring them into synergy with Jesus’ teaching through his lectures must have gone a long way open the hearts of others. Finally, through a difficult year-long process of intensive discussion the Wonju Group came to an agreement on transitioning the cooperative movement in Wonju into a Life Movement rooted in Donghak philosophy.

The new direction was expressed in the Wonju Report in 1982 which was written on behalf of the group by Kim Ji-ha. The report criticised capitalist and socialist industrial models of civilisation as equally destructive and incapable of producing a fair and sustainable society and called for an alternative movement for the transformation of society centred on the concept of Life. Publication of the Wonju Report was followed by the organisation of training courses and lectures and a study tour in 1984 to cooperatives in Japan. In 1985 the Wonju Consumer Cooperative was created, with Park Jae-il as chairperson, to organise store-free direct trade with organic farming communities. The store in Seoul, Hansalim Nongsan, followed in 1986 and in 1987 the Hansalim Community Consumers’ Cooperative and the Hansalim Producers’ Association were founded. This led to the formation in 1988 of the Hansalim Community Consumers Alliance in Seoul with 70 members and the Hansalim Producers’ Council in Wonju with 70 farmers.

3.4.2 A Manifesto

With the first practical implementations of the Life Movement in place, the Wonju Group34 formed the Preparatory Group for the Hansalim Study Gathering which held five meetings to discuss and diagnose the problems in Korean society and consider how the Hansalim Movement should respond. These were followed by eleven study sessions and four discussion meetings to review contemporary social movements around the world, study various economic, philosophical and social theories, and survey Korea’s own cultural history of cooperation in search of the future direction for Hansalim. This process culminated in the publication of the Hansalim Manifesto in 1989 which set out the philosophical foundation of the movement and outlined the direction of its practical implementation.

It is worth listing the chapters of the book that was compiled with the Hansalim Gathering research reports to give a sense of the scope of their thinking and the calibre of people involved. Each chapter was a report to the Hansalim Gathering that was debated in turn and sifted for relevant insights to be included in the Hansalim Manifesto. As such, they provide a map of the philosophical, socio-cultural and scientific ideas that undergird the Manifesto and the philosophy of the Hansalim Life Movement. It is these ingredients, along with the decades of experience in the cooperative and credit-union movements and the fight against dictatorship which have shaped Hansalim’s identity and which provide us with a rich collection of Resources for exploring the potential for a New Cooperative identity.

| Report Title | Author | Role and affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Part 1: Ecological Crisis and the Green Movement | ||

| 1. The Planetary Crisis of Disintegrating Ecosystems | Kim Sang-jong | Professor, Department of Microbiology, Seoul National University |

| 2. Twentieth Century Western Environmentalism | Yi Sang-moon | Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Seoul National University |

| 3. Green Movements and Green Parties in the West | Kim Jae-geom | Hansalim Community Consumer Cooperative |

| Part 2: Understanding Traditional Ideas and New Worldviews | ||

| 4. Ecological Communism | Kim Yong-ok | Former Professor of Philosophy, Korea University |

| 5. Meaning of Hanullim35 in Donghak36 | Seo Jeong-tok | Hansalim Gathering Research Committee member |

| 6. Poong-su 37 and the Anti-pollution Movement | Choi Chang-jo | Professor, Department of Geography, Seoul National University |

| 7. Dure38 and Nong-ak39 | Sin Yong-ha | Professor, Department of Sociology, Seoul National University |

| 8. Natural Sciences and Understanding Life | Jang Hui-ik | Professor, Department of Physics, Seoul National University |

| Part 3: The Life Movement as a New Alternative Movement | ||

| 9. Hansalim as a Life Movement | Choi Hye-seong | Hansalim Gathering Research Committee Chair |

| 10. Donghak Social Activism and the Hansalim Movement | Kim Ji-ha | Poet |

3.5 Understanding the Manifesto

The Hansalim Manifesto is quite long for a manifesto (over 20,000 words) and contains many complex ideas. It is significant not only as providing the spiritual foundation for the Hansalim movement but also for the wider Life Movement in Korea and its influence reaches to other cooperatives and movements across the country. It has been translated into Japanese, Chinese and Thai and, most recently, into English in 2021.40

The Manifesto is presented in five chapters:

- The Crisis of Industrial Civilization

- Ideology of the Mechanistic Model

- Holistic Life’s Creative Evolution

- Cosmic Life Enshrined in Humans

- Hansalim

3.5.1 The Crisis

The first chapter describes the symptoms of contemporary industrial civilization with equal disdain for capitalism and communism. On the one hand, in the Capitalist world, “The technocratic system that rules over the control of matter, energy, and information now has the ability to manipulate and control human consciousness…” And it now appears that “capitalist society has achieved material growth, but exhibits an innate tendency towards totalitarianism” and41 On the other hand, in the Communist system “the dictatorship of the working class has come to mean the concentration of absolute power in the party… instead of encouraging the initiative and autonomy of the people, the party and its leaders now demand their conformity and obedience to the system, and force them to be subordinate to the machine.”42 Both systems, Capitalist and Communist, are underpinned by the same foundation of technological industrialism, “a totalitarian world that uses technology and machines to dominate and control humanity and nature.”43

Industrial civilisation is a civilisation of death:

“turning life into a machine, an autonomous being into a possession, a subject into an object, a master into a slave, knowledge into technology, freedom into conformity, labor into commodity, waste into a necessity, production into destruction, prices into value–it is by so perverting things that industrial civilization has been able to create a world of its own. Moreover, with humanity divided against humanity, humanity against society, humanity against nature, industrial civilization is a world of conflict, where all battle against all as bitter rivals.”44

The symptoms of this civilization of death are the threat of nuclear war, the destruction of the environment, resource depletion and population explosion, endemic diseases of affluence and societal dysfunction, economic cycles of inflation, recession and unemployment, and domination by a centralized technocracy. These symptoms are all manifestations of the same issue. That is, the Manifesto claims, a faulty worldview that has lain at the heart of Western civilization since the 17th century,

3.5.2 Its Cause

The second chapter argues that the world order of the West “was created by the philosophy of the Enlightenment, empirical science, the industrial revolution, and the people’s revolution”45 “In Descartes’s philosophy, Newton’s physics, and John Locke’s views of society, humans and matter are understood as isolated, discrete, and atomistic entities; nature, society, and the universe are explained accordingly, in terms of a mechanistic model.”46

“Going further, Western rationalism, empiricism, and industrialism placed emphasis on analytical knowledge over intuitive wisdom, dissection over synthesis, confrontation over harmony, competition over cooperation. Such a one-sided orientation and perspective helped produce a culture lacking in balance—a balance of humanity and nature, reason and emotion, existence and values—and precipitated the crisis of industrial civilization, with social, political, and ecological confrontations and conflicts.”47

According to the Manifesto, the features of this mechanistic worldview include the following.

- Scientism - an un-justified faith in science as the only source of truth;

- Dualism - a dualistic ontology that separates mind and matter;

- Determinism - a Newtonian model of the universe as mechanistic and deterministic;

- Biological reductionism - a mechanistic understanding of life processes;

- Behaviourism - a mechanistic model of the human mind and society.

- Economism - reduction of social phenomena to the logic of monetary transactions in a single-minded pursuit of linear growth.

- Anti-ecological philosophy of nature - taking nature as an object of conquest.

This worldview, grounded in Newtonian science, Cartesian dualism and biological reductionism, casts humanity in the role of mere parts in a global socio-technical-economic machine which, although ostensibly designed to free humanity by enslaving the nonhuman world, has instead made humanity slaves to the ‘civilisation’ it has created which now drives the nonhuman world into a chaos of disorder. The core argument of the Manifesto is that the root the contemporary crisis is this outdated and faulty worldview grounded in the machine metaphor, that sees the universe as mindless mechanism subject to the dismal law of entropy that energy and matter irresistibly tend towards disorder and decay:

“Industrial civilization uses the principle and order of a machine to oppress and dominate life represented by humanity and nature, and pursues growth in the name of rationality and efficiency, only to make itself more massive, more professionalized, and more centralized…. The world of the machine is a dead world governed by the principle of entropy.”48

3.5.3 Reality

In chapter three, taking the concept of entropy as a jumping off point, the Manifesto draws on the move from reductionism and classical mechanics towards holism and complexity associated with the New Science movement and environmentalism of the 1980s to propose an alternative understanding of the world. While the theory of thermodynamics predicts the inevitable increase in entropy over time – the eventual decay of a material universe into the final equilibrium of heat death – a quite different conclusion can be drawn from the perspective of the creative evolution of a cosmos in which Life (as consciousness rather than mechanical force) is the operative principle. The Manifesto sees the cosmos as an open, complex and adaptive system of autonomous interdependent agents in a constant process of coevolution and dynamic disequilibrium in which divine spirit is inherent within all things:

“Spirit does not reside only in humans or life forms as such, but permeates everything in the universe, while remaining the source of all of life’s activities.”49

In an open system imbued with spirit:

“irreversible time, entropy, actually becomes the creator of order… So the universe remains alive with movements: its true image is a boundless spread of vast cosmic life, which evolves by encompassing all living beings.”50

The implication, then, is that any human civilisation that aspires to survive and thrive must find a way to live in symbiosis with this cosmic Life instead of trying to force life into an artificial closed system for the sake of an illusion of control.

In the third chapter, of the Manifesto, the concept of entropy and the second law of thermodynamics are used to construct a theory of a dynamic cosmos which directly contradicts the Newtonian mechanistic model by drawing on contemporary ideas in New Science and ancient Korean thought. According to the Manifesto, industrialised civilisation operates as if it were a closed system, underpinned by a concept of time as absolute, uniform and reversible. In contrast, the theory of thermodynamics conceives of time as relative, non-uniform and irreversible. In a closed system, according to the second law, entropy (disorder) accumulates tending towards a static equilibrium state of motionlessness and death. In an open system, through self-organising processes and continual interactions, time and entropy give rise to higher dimensions of order as the web of living beings coevolve with cosmic life in a continual “becoming”.

The contrast between the machine model and life model of change is described in six pairs of dichotomies and a final statement about spirit. First, while the machine is an artificial “being” made for a pre-defined purpose, life exists in a mode of “becoming” as it grows and matures according to its own internal identity. Second, the machine is a simple collection of replaceable parts but life is a whole made up of nested interdependent wholes which simultaneously express individuality and collective unity. Third, the machine is ordered by a rigid design while life displays a flexible interaction between order and consistency on the one hand, and autonomy, irregularity and diversity on the other. Fourth, while the machine is a heteronomous tool (a means to an end), life is autonomously motivated by internal intentions which operate within, but not completely determined by, the limits of the environment. Fifth, as opposed to the closed system of the machine, life is an open system of mutual exchanges of matter, energy and information that is not only self-renewing but also creative in its interaction with the environment. Microcosm and macrocosm coevolve to continually transcend their previous limitations. Sixth, the machine operates according to linear cause and effect. Life thrives on disequilibrium, characterised by non-linear circulating feedbacks that provide the creative capacity to overcome former limitations and adapt to external and internal disturbances. Finally, implying the non-dualism of ancient Korean shamanism, the Manifesto argues that life is “spirit” (Hanul or cosmic divinity) and that this creative spirit permeates all things. Matter is seen not as the opposite of spirit but as co-inherent with it and expressing another aspect of the divine spirit alongside the development of reflexive consciousness and culture that characterises the human spirit:

“The divine universal mind is present within the human spirit”51

3.5.4 A Solution

While western environmentalism and the new science movement provided the basis of their critique of industrialised civilization, the resources for imagining an alternative future were drawn from Korean history, specifically from the ancient culture of Korea and the philosophy of Donghak.

Chapter four introduces seven key ideas which form the core of Hansalim’s Life Philosophy. These ideas are grounded in the Qi cosmology of the Dao (Way) and Yin/Yang but presented in a uniquely Korean way through the language of ancient Korean thought. The Korean word “Han” refers to the life of the universe as a unity of individuals gathered together as cosmic whole; “the oneness–the”han”–of cosmic life undergoing evolution.”52

Therefore:

“From “han” or one cosmic life, the sky, land, and people are created, become imbued with life of their own, and then become united again with cosmic life as one. Thus, “han” means being everywhere and not leaving out anything.”53

This concept was given fresh clarity in the philosophy of Donghak which gave Han the name Hanullim in reference to a personal immanent God as an object of faith and devotion and the source of morality. Donghak taught that Hanullim dwells within all people; an idea communicated in the phrase Innaecheon (인내천 / 人内天) which translates literally as “within people is heaven”. The central incantation of Donghak is a prayer to be filled with the Divine Spirit for the sake of the peace of the world and it main practices are contemplative prayer (or meditation) and actions of justice and service to cultivate the seed of Divine Life within.

The Manifesto draws seven key concepts from Donghak which can be summarised as follows:

- Divinity: All things are divine because Hanullim lives in all things, animate and inanimate. Therefore the proper attitude to one another and all the world is one of reverence as to God.

- Enshrining: To be truly human is to enshrine Hanullim within by keeping a pure mind and behaving justly.

- Nurturing: The seed of Divine Life within can only grow to fullness as we work together in mutual cooperation with others to nurture that Life in all things with reverence.

- Rice: food is the fruit of Hanullim in the cooperation between the land, the sky and the effort of many people (“the sweat of our neighbours”). Rice (or food) is therefore a symbol of the cosmic and the human community. It must therefore be received prayerfully with a willingness to repay those who produced it in a mutual exchange of energy and spirit.

- Embodying heaven: as “carriers and cultivators of Hanul” we are obliged to act ethically, socially, and ecologically so that the world becomes more heavenly (or “Hanul-like”); to mend the world.54 The is expressed as:

“an ethical and political battle fought against an order that allows killing and oppression, a socioeconomic battle against alienation and conflict, a verbal and psychological battle against the culture of manipulation and deception.”55

- Dawn: the old order needs to be dismantled for the new order of life to be created in “the dawn of a new world embodying heaven”.56 This cannot be achieved by forced revolution but by cooperating with the “flow of evolution whereby the old naturally gives way to the new”57 through a personal and collective awakening as people observe the practical examples of those who are already embodying the mind of Hanullim.

- Becoming: to perceive the truth we must break free from dualistic thinking to embrace the intuitive logic of bul-yeon-gi-yeon (or “not so yet so” / 불연기연 / 不然其然). This enables us to recognise the cosmos as a complex whole of ‘becomings’ which are simultaneously fully themselves and not-yet what they will be, individuals whole in themselves and also parts of an evolving whole. It requires we move beyond analytic thinking towards trusting our intuition about the world.

3.5.5 Hansalim

The final chapter of the Manifesto attempts to set out how these concepts or principles define Hansalim. In summary, Hansalim is:

- Cosmic awakening about life: to recognise the position of humanity as a part of the vast tree of divine cosmic life while also bearing a unique responsibility as carrying that cosmic life and the mind of Hanullim latent within their hearts.

- Ecological awakening about nature: to recognise that the earth, too, “possesses a mind of its own as Gaia” and that the matter itself is imbued with spirit and consciousness so that we have a responsibility to live in symbiosis with the earth.

- Communal awakening about society: to recognise that humans are born into community and survive through cooperation “in an endless exchange and circulation of matter and energy, information and knowledge, emotion and spirit” and that “when people treat other people as Hanul, they can make the world sublime”58

- Cultural movement: to promote the worldview of life and the values and lifestyle associated with it throughout society.

- Life-nurturing social practices: to resist “political regimes, technocrats and big corporations that are anti-ecological and against community”59 through non-violent creative activities promoting love, peace and life.

- Daily practices for self-actualization: mind and body training to purify the mind and the life energies of the body so as to walk in step with the Spirit, to ’become rice” for others and to nurture life in all things.

- Life unifying activities: to work for the unification of emotion and reason, analytic knowledge and intuitive wisdom, body and spirit, individual and community, nature and humanity. And also for the reunification of the Korean people and other divided peoples.

The Manifesto ends with a quote from the founder of Donghak, Choe Je-u:

The boundless principle, boundlessly beheld,

Is it not, inside this boundless enclosure,

boundless me?

Sam-Woong Kim, Biography of Jang Il-Soon: The Beautiful Life of Muwidang, ed. Muwidang People (Seoul, Korea: Dure, 2019).↩︎

E Patricia Tsurumi, “Colonial Education in Korea and Taiwan,” in The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945, ed. Ramon H Myers and Mark R Peattie (Princeton University Press, 1984), 275–311, https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=HWbcDwAAQBAJ.↩︎

Hyung-Mi Kim, “The Experience of the Consumer Co-Operative Movement in Korea: Its Break Off and Rebirth, 1919–2010,” in A Global History of Consumer Co-Operation Since 1850, ed. Mary Hilson, Silke Neunsinger, and Greg Patmore (Brill, 2017), 353–78, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004336551_020.↩︎

E-Wha Lee, Korea’s Pastimes and Customs: A Social History, trans. Ju-Hee Park (2001; repr., Paramus, New Jersey: Homa & Sekey Books, 2006).↩︎

S Lee, “Role of Social and Solidarity Economy in Localizing the Sustainable Development Goals,” Int. J. Sustainable Dev. World Ecol. 27 (January 2, 2020): 65–71, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2019.1670274.↩︎

Kim, “The Experience of the Consumer Co-Operative Movement in Korea,” 2017.↩︎

Yi-Kyung Kim, “The Formation and Development of the Korean Cooperative Movement Under Japanese Colonial Rule - Focus on Concepts, Participants, and Solidarity” (SUNGKYUNKWAN UNIVERSITY (성균관대학교 일반대학원), 2022), http://www.riss.kr/search/detail/DetailView.do?p_mat_type=be54d9b8bc7cdb09&control_no=dc834242f8ef0680ffe0bdc3ef48d419.↩︎

Seong-Bu Kim et al., eds., 100 Years of the Korean Co-Operative Movement Vol. 1 (Seoul, Korea: Autumn Morning, 2019).↩︎

Personal communication from a relative of a Wonju Hansalim founder.↩︎

Currently, 150,000 people, or 44% of Wonju’s population of 360,000, are credit union members.↩︎

Larry L Burmeister, “The South Korean Green Revolution: Induced or Directed Innovation?” Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 35 (July 1987): 767–90, https://doi.org/10.1086/451621.↩︎

Yooinn Hong, “Regionally Divergent Roles of the South Korean State in Adopting Improved Crop Varieties and Commercializing Agriculture (1960–1980): A Case Study of Areas in Jeju and Jeollanamdo,” Agric. Human Values 38 (December 2021): 1161–79, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10232-y.↩︎

Sok-Yong Hwang, Jae-Eui Lee, and Yong-Ho Jeon, Gwangju Uprising: The Rebellion for Democracy in South Korea (London, England: Verso Books, 2022).↩︎

Quoted in, Kim, Biography of Jang Il-Soon, 2019, 260–61, translation J. Dolley.↩︎

Carl F Young, Eastern Learning and the Heavenly Way: The Tonghak and Chondogyo Movements and the Twilight of Korean Independence (University of Hawai’i Press., 2014), http://www.jstor.com/stable/j.ctt13x1k6b.2.↩︎

Haeyoung Seong, “The basis for coexistence found from within: The mystic universality and ethicality of Donghak (東學, Eastern learning),” Religions 11 (May 23, 2020): 265, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11050265.↩︎

Kim, Biography of Jang Il-Soon, 2019, 197–98, translation J. Dolley.↩︎

Muwidang, “Why Hansalim?: Summary of the Speech Given by the Late Jang Il-Soon at the First Training Session for Hansalim Activists Held in Seoul on 11 April 1991,” Green Review, 1994, translation J. Dolley.↩︎

Jang Il-soon - lay Catholic leader and educator; Kim Ji-ha - poet and writer; Park Jae-il - agrarian activist and former president of the Catholic Farmers’ League; Choe Hye-sung, ??; Kim Young-won - leader of the Christian Peasant Movement and first president of the Hansalim Producers’ Association; Lee Soon-ro - housewife and first chair of directors of Hansalim Community Consumer Co-op; Kim Min-gi - Song Writer of the famous ‘Morning Dew’; Choe Hee-wan - Prof of Dance at Busan University; Park Chang-soon - broadcaster and producer of education programs on national TV; Kim Young-ju - Chair of Wonju Credit Union Training Centre; Kim Sang-chong - Prof of Microbiology at Seoul National University; Choi Sung-hyun - Natural Farmer at ‘Nature School’; Cho Seung-Sam - from Gwangju; Park Meng-su - first director of the Mosim and Salim Research Institute.↩︎

Hanullim is the Donghak word for God or Divine Spirit.↩︎

Donghak is a Korean indigenous religion founded in 1860.↩︎

Poong-su refers to the ancient Korean practice of geomancy. The word is as composite of wind (poong) and water (su) in the same way as the Chinese word fengshui.↩︎

Dure refers to organisations created by Korean peasants throughout the Joseon dynasty to organise farming and other community activities, rather like a village cooperative.↩︎

Nong-ak refers to the culture of music and dance created by peasant farmers in Korea since ancient times.↩︎

Hansalim, Hansalim Manifesto (English Version) (Mosim; Salim Research Institute, 2021), 18–20.↩︎

There are ten taboos listed under the activity of embodying heaven which are: “1. Never deceive life 2. Never be arrogant before life 3. Never wound life 4. Never disrupt and disturb life 5. Never kill life before its time 6. Never defile life 7. Never starve life 8. Never destroy life 9. Never hate life 10. Never enslave life.” (p. 100)↩︎

Donghak calls this dawn “Gaebyeok” (개벽 / 開闢).↩︎