1 What is Hansalim?

Final draft

In 1986 pro-democracy protesters were out in the streets fighting with police and trying to escape tear gas.1 Since seizing power in a military coup in 1961, General Park Chung-hee presided over 18 years of military rule. Following his assassination in 1979 and another coup, General Chun Doo-hwan installed himself as president, leading what was essentially a continuation of the military regime in the face of growing mass protests calling for democratic government.2

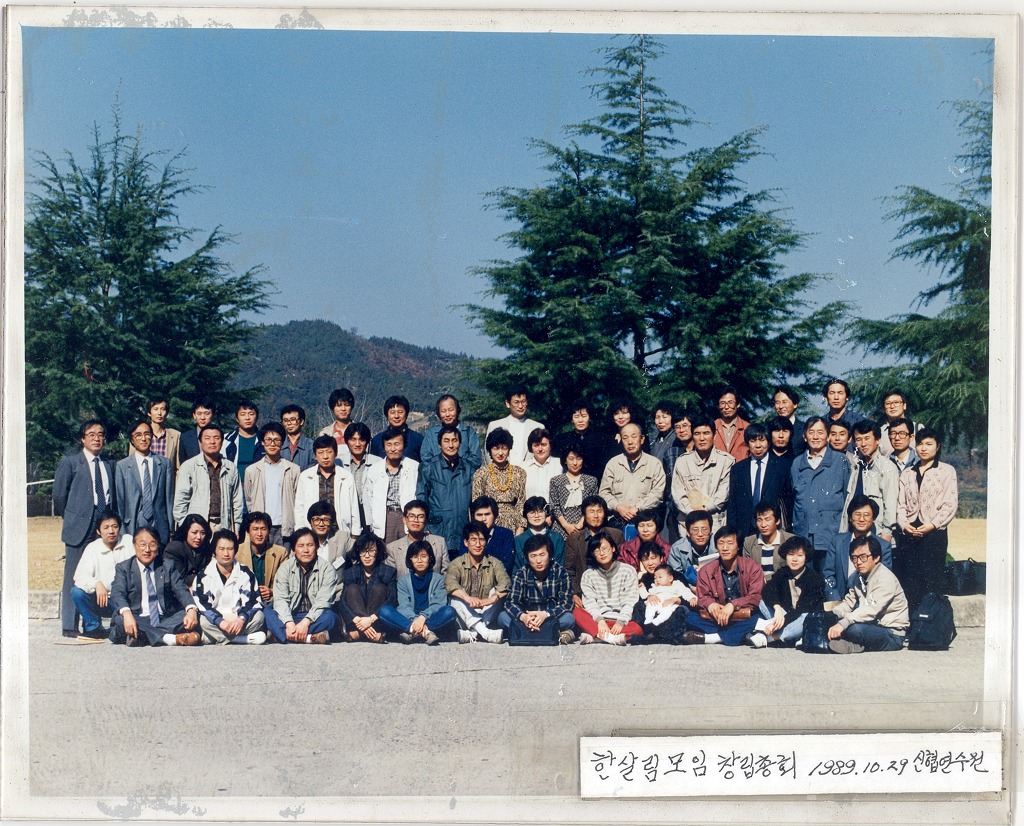

In the midst of such turmoil, a small group of farmers and activists opened a small rice store in the centre of Seoul. In light of the chaotic political situation, this was seen by their fellow pro-democracy activists as a betrayal. However, the creation of that first store, called Hansalim Nongsan, was actually a radical act of resistance and hope in the face of political uncertainty. The men and women who opened Hansalim Nongsan belonged to a small cooperative of producers and consumers in the city of Wonju, about an hour away from Seoul, and that store represented a first step in launching an ecological alternative movement that had been gathering support in Wonju and beyond since the late 1970s. Its founders where known as the Hansalim Moim (한살림모임, Hansalim Gathering).

1.1 A movement, a manifesto, a business

The Hansalim Moim were a diverse collection of Catholic Farmers, urban housewives, pro-democracy activists, artists, poets and scholars who had been involved in the credit union movement in Wonju that was founded in the 1960s. They had witnessed the fundamentally destructive tendencies of capitalist and socialist industrialisation and they were looking for an alternative in the cooperative movement. However, they recognised that cooperatives were also vulnerable to the same fundamental mistake that lay at the heart of industrial civilization. That mistake was to assume a materialist, mechanistic view of the world which viewed humans and all life as replaceable parts in the machine of economic growth. It was this worldview, they argued, that gave rise to the characteristics of domination, alienation, separation and oppression in modern society.

As an alternative, they proposed a worldview founded on the sacredness and interconnectedness of all life. The first version of this worldview or eco-philosophy was outlined in the Wonju Report in 1982. As the movement began to grow the Hansalim Moim set up the first Life Cooperative in Wonju in 1985 and the Hansalim Nongsan rice store in Seoul a year later.3 In this way, the Wonju Coop formally brought together organic farming and direct trade with the equal participation of consumers and producers.

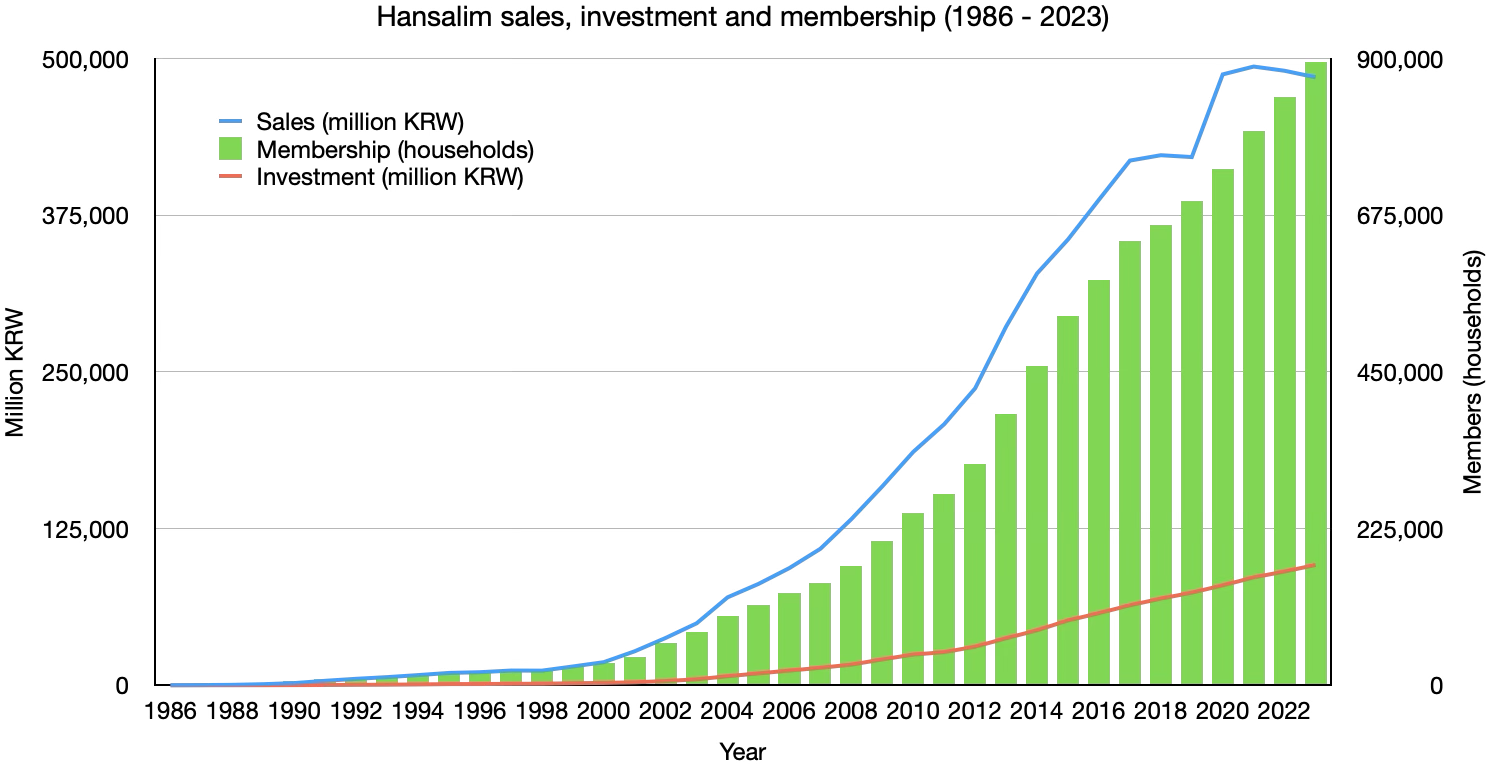

Soon after, the Hansalim Community Consumers Union was set-up in Seoul with 70 members to trade directly with the Hansalim Producers Association that was set up with 70 farming households. Next, the Hansalim Moim (한살림모임, “Hansalim Gathering”) hosted a year long process of study and discussion to develop the Hansalim Manifesto which was published in 1989 and which formally launched the Hansalim Life Movement. From this small beginning, the movement quickly expanded as other cooperatives and farming communities joined from across the country and consumer membership grew.

By 1990 there were four local life Cooperatives with over 5,500 members and within just over another 10 years membership had grown to over 40,000. That is when things really began to take off and by 2008 there were 19 Life Cooperatives managing 84 stores for their 170,000 members. In 2023 Hansalim’s 27 Life Cooperatives and 15 Producer Federations handled annual sales of 485,066 million KRW (324.3 million euros) through 240 stores, an online store and a mobile app.4 From these sales, 330,610 million KRW (221 million euros) were returned to the 136 producer communities. That is nearly 70%! So what kind of business model has Hansalim created that provides those returns to producers while covering the shared business operations and funding a whole range of movement activities from the remaining 30%? And what lies at the heart of this unusual way of doing business?

1.2 Built on a relationship of mutual care

At its simplest, the Hansalim Life Movement is a relationship of mutual care and responsibility between rural and urban communities. The core of Hansalim’s approach is expressed in this phrase: “Let the producer take responsibility for sustaining the consumer’s life and the consumer for sustaining the producer’s livelihood”.5 However, this mutual responsibility is about much more than simply direct sales as it also encompasses a shared commitment to protecting and restoring ecosystems and working for wider social and cultural change towards justice and peace.

This expansive goal is captured by the name itself: “Hansalim” (한살림). The first part of the word, ‘Han’ (한) contains two sets of paradoxical meanings. It expresses, firstly, a paradoxical double sense of being collectively one and individually one and, secondly, of spreading out as one and gathering in as one.6 In ancient Korean philosophy ‘Han’ refers to the divine Spirit or life of the universe which permeates all things, living and inanimate, and integrates the universe into an evolving cosmos.

The word ‘Salim’ (살림) has two related meanings. The first is ‘housekeeping’ which implies parental care, homemaking, food preparation, hospitality. It is perhaps the most practical of all human activities and is the bedrock of human survival and flourishing. The second meaning develops from this practical sense the philosophical concept of ‘nurturing’ which has the connotation of saving and restoring, bringing back to life, vivifying.7

So we see that the word ‘Hansalim’ expresses a relationship and an action. It encompasses the goal of nurturing or reviving all things, that is bringing all into a flourishing shared life together. In fact, the word ‘Hansalim’ is often used as a verb as when members encourage each other by saying “let’s Hansalim!”

Among Hansalim members, the word “Salim” is used to express their purpose in all their activities. So the collective mission of Hansalim is summed up in four phrases that each incorporate this word Salim.

The first, ‘Nurturing Food’ (밥상살림 — bapsang-salim) refers to the goal of providing consumers with safe, healthy, eco-friendly food and other household goods and this defines the responsibility that producers adopt for the life of consumers. The word in Korean directly translates as nurturing the dining table and the significance of this is that it refers to the act of sharing a meal, not simply consuming food. Second, ‘Nurturing Agriculture’ (농업살림 — nongup-salim) refers to the goal of securing stable and sustainable livelihoods for producers and this defines the responsibility which consumers adopt for the livelihoods of producers. Third, ‘Nurturing Life’ (생명살림 — saengmyeong-salim) expresses the responsibility of care for others (human and non-human) which producers and consumers together share and which is worked out through outward focused activities such as promoting eco-friendly farming, environmental campaigning, education, social welfare projects, and inward contemplative and reflective practices. Finally, ‘Nurturing Community’ (지역살림 — jiyeok-salim), emphasises the need to strengthen local community resources and relationships and to reach out to neighbours in need.

So how are these values put into practice? I’m going to tackle this question from bottom up, first from the rural or producer perspective and then from the urban or consumer perspective before describing the alternative economic system that brings them together.

1.3 In the form of a multistakeholder cooperative

The producer community is the smallest level of organization in Hansalim. In these communities farming is done together by a group of family farms who partner with one another to plan and coordinate their production, share knowledge and labour, and manage shared facilities and equipment. To join Hansalim as a producer, you would join one of these communities and receive training in eco-friendly farming and Hansalim’s production and processing standards.

There are 136 producer communities which cultivate a total of 11,300 acres (4,572 ha). In addition to the producer communities there are 110 processing units which process raw materials from Hansalim’s producers as well as seafood and other products from local organic and environmentally friendly sources.8 The producer organizations are brought together into 15 regional federations with their own elected representatives which together form Hansalim’s National Producer Federation with their own elected president and employed staff. Many of these regional federations pool resources to run local distribution hubs with their own processing facilities and some have created complex systems to process and re-circulate farm wastes as inputs between multiple local farms.

(map of producer communities)

When you join Hansalim as a consumer you become a member of your local Life Cooperative (one among 27 as of 2024). The word “life” is significant because these cooperatives are not like the conventional consumer cooperatives that you would encounter in Europe or America. Their focus is not only responsible consumption but also seeking to live together in solidarity with one another and with producers and rural communities. Each Life Cooperative in Hansalim is a democratic autonomous organization formed by members to carry out collective activities, set-up and run Hansalim stores, organize charitable, cultural and educational activities and the joint activities between rural producers and urban consumers.

(map of Life Coops)

Together, the producer communities and federations and the Life Coops form a federation of cooperatives, associations and businesses linked together through a shared business federation and the Hansalim Federation with its support organisations including a research institute, the Hansalim Foundation, solar power coop, publishing house, training institute and peer-to-peer finance platform. So how does this business work?

1.4 Creating an alternative economy

In simple terms, the Hansalim business model can be described as a contract-based direct sales arrangement in which prices and quantities are agreed annually in advance by producers and consumers with support from Hansalim’s employees. However, it is also very flexible in ways that are designed to support the needs of producers.

A system designed for producers

There are four key features of Hansalim’s business model. Firstly: flexibility of production. Hansalim’s production system allows for a relatively wide range of production philosophies and techniques among member producers to ensure that producers have maximum autonomy. For example, one producer community might prefer a relatively simple style of organic farming with a small number of crops while another aspires to build a complex system of circulating agriculture with a large diversity of crops and livestock supported by recycling of farm wastes from one part of the system as inputs to others. Still others, especially fruit producers, might find it impossible to grow without a limited use of home made natural pesticides. A dogmatic insistence on a single farming philosophy would exclude many farmers who might be unable to follow a one-size-fits-all system in the face of local conditions or other resource constraints. Hansalim’s more flexible approach removes a significant barrier to entry for farmers who would otherwise need to spend a long time learning new techniques before starting to earn an income. This brings the added advantage that farmers who want to transition from conventional to organic farming can do so in a staged process while still making a living. However, it also creates a problem. How to maintain the trust of consumers when the diversity of production techniques is so wide?

This brings us to the second feature of Hansalim’s business model: simple and honest labeling. Transparency with consumer members is ensured through Hansalim’s own labelling system. For example, primary agricultural products are labelled under four main categories:

- Organic (which would include conventional organic, permaculture and EM techniques);

- Pesticide-free (when crop types and local conditions make it non-viable to exclude use of fertilizers);

- Low pesticide (for certain fruit crops which would be prohibitively difficult to grow without a limited use of pesticides);

- Domestic (for miscellaneous grains such as barley or black bean which are used as raw ingredients in some processed goods and feed for livestock).

For all four categories Hansalim’s standards are stricter than the national safety standards and products are tested regularly for residues, contaminants and radiation as appropriate to protect trust between consumers and producers.

To complement the flexibility and transparency of production methods the third feature - flexibility of supply - enhances the autonomy of producers and provides some added resilience to the system. Hansalim producers are not locked-in to exclusive supply contracts but have the freedom to supply whatever proportion of their crop to Hansalim they wish while simultaneously supplying through other channels such as government purchasing schemes for school meals. This applies to each producer community and also to each member of each community. So one farmer might supply 30% of their produce to Hansalim through their community while selling the rest through local government procurement for school meals. Or a producer community might sell Hansalim branded grapes through the Hansalim Federation while selling grape juice through another market under their own brand.

Finally, for an additional level of flexibility, the contract-based system is supplemented by demand-based supply arrangements to allow greater flexibility for producers.

Taken together, these four features of Hansalim’s business model mean that, within and between producer communities the level of specialization or circular integration and the combination of sales channels are all decided by the producers themselves. This makes for an astonishingly diverse range of production operations each tailored to the local soil and climate conditions and preferences of producers themselves, while ensuring a stable guaranteed income to as many farmers as possible.

These images show just a tiny snapshot of some of the different farming landscapes, crops and approaches which form Hansalim’s complex agricultural systems. The system of labelling helps provide a sense of order to this complexity for the sake of Hansalim’s consumer members and also facilitates the progression of Hansalim producers further away from conventional farming methods towards progressively more eco-friendly alternatives. Let’s look at the overall share of production according to production type, crop type and supply type. The following graph, Figure 1.2, shows the flow of goods by tons.

On the left you can see the four labelled production types of organic, pesticide-free, low-pesticide and domestic. In the centre, the crop types are divided into vegetables, staple grains, roots and tubers, fruit, and miscellaneous grains. On the right, crop types are categorized into supply type as either contract-based or demand-based supply. If you interact with the graph you can see the number of tons of each combination. The majority of production is organic and this accounts for most of the vegetable cultivation, almost all staple grains and root and tubers. These crop types are almost entirely supplied on a contract-basis. Pesticide-free production accounts for some vegetable supply, a fraction of staple grains and some fruit crops. It is in fruit cultivation that a higher proportion of crops are cultivated according to ‘low-pesticide’ standards. This is because many fruit crops are especially vulnerable to pests and would not be viable for producers without some use of non-synthetic pesticides. Miscellaneous grains are mostly produced under the domestic label and supplied on a demand-basis.

So what happens to the revenue from the sales of Hansalim’s range of over 4,000 products? As I mentioned above, until recently, with margins well below 30%, Hansalim was able to return 73% or more of the product price to the producers. Now, following several years of rising costs and worsening impacts of climate change the margin has come under increasing pressure and currently stands at just over 31% which leaves almost 69% for producers. This table Figure 1.3 shows the breakdown of what the margin covers.

| Division | Rate | Subdivision | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hansalim Federation | 0.81% | Subscription fees | 0.55% |

| Service revenue | 0.26% | ||

| Hansalim Business Federation | 8.86% | Business share rate | 8.61% |

| Production support fund | 0.165% | ||

| Price stabilization fund | 0.085% | ||

| Member Life Coops | 21.7% | Regional margin rate | 21.6% |

| Production stabilization fund | 0.1% | ||

| Gross margin rate (GPR) | 31.37% | ||

This margin structure is virtually the reverse of conventional market distribution which usually takes a 50 - 70% margin. So what does this distribution of revenue look like from the point of view of the Life Coops, producers and the federal organisations? The following chart, Figure 1.4, shows the flow of value (in euros) from the sales of goods (on the left) through each Life Coop (center) to the share of revenue provided to each category of organization (right).

You will notice that the vast majority of sales are of ‘federation goods’ which are those supplied through the business federation’s distribution channels. A much smaller percentage of sales are accounted for by so-called ‘local goods’ which are supplied independently from Hansalim’s central distribution system. The central column of the chart looks a bit messy, but the point is that the majority of sales are through shops managed by the Life Coops in Seoul and Gyeonggi (the province surrounding Seoul) which together form the largest and densest population centre in Korea. On the right hand side you can see that the share of revenue returned to producers is by far the largest, while the margin covers the budgets of the Life Coops and finally the Business Federation and the Hansalim Federation.

This distribution revenue is achieved through a combination of:

- Recovered costs from distribution by removing the multiple opportunities from profit gauging by intermediaries;

- Prices set to reflect the true costs of production; and

- Economies of scope and scale achieved through shared business activities and collectively owned capital at local, regional and national levels.

After providing for producers’ livelihoods, what then does the remaining 30% pay for?

A different kind of consumer experience

The largest portion (21.7%) goes to the Life Coops themselves to cover the costs of running stores, handling local distribution and their various educational, participation and engagement activities. Life Coops are autonomous member owned businesses which run the Hansalim stores in their local areas. They decide when and where to open new stores, how to manage them and how to organize local distribution options such as home delivery. Stores are usually run by an employed manager and the Life Coop’s Store Activists (consumer members who are trained and paid to staff the stores) and products are ordered through the Hansalim Business Federation and delivered from their national logistics centre.

In a Hansalim store you can buy virtually everything you need from food to household goods and even cosmetics. Almost all these products are made by Hansalim producers and processors with a few exceptions for some household items and a handful of fair trade products. Hansalim branded sales through the business federation are supplemented by local goods sourced by each store according to the decision of each Life Coop. What this means is that there is usually just one type of everything you need rather than multiple brands of the same product so the shop size is relatively small compared to a regular supermarket. Here are a few examples of the products that are available in my local Hansalim store.

Hansalim stores also differ from a conventional supermarket in another way. They often provide the venue for member activities and encounters between consumers and producers facilitated by the Life Coop’s Organizing Activists (members who are trained and paid to organize opportunities for consumers and producers to meet each other and share food and other activities together). From the beginning of Hansalim, relationship building among consumers and between consumers and producers has been a top priority.

There are various ways consumers can build community together and participate in the livelihoods of producers. Neighbourhood meetings and small groups provide a context for consumer members to learn and build relationships through reading groups, cooking classes, social activities, and environmental activism etc. ‘Helping hands’ visits are organized by Activists to bring members to help producers with farming activities such as planting, weeding and harvest and to join in with traditional rural rituals and share meals together. Community work is also an important shared activity in which members and producers raise money for charitable causes, donate food to people in need and provide education and support to marginalized groups. Consumers often visit the producer communities for local festivals or just to see the farm, share a meal and get to know each other. Producers also visit stores to introduce their new products and many develop special relationships with particular Life Coops as well as participating in Hansalim conferences and multistakeholder committees.

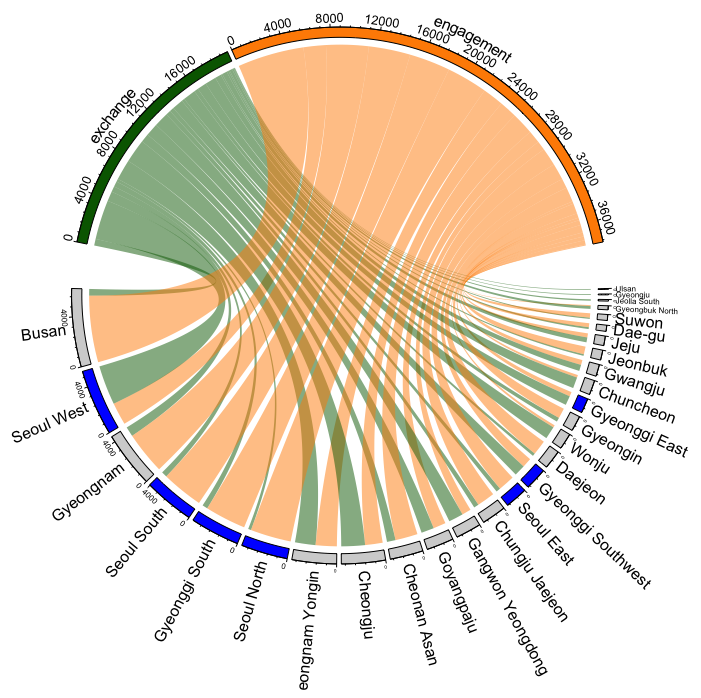

Each of these activities are supported by funds allocated in the budgets of the Life Coops and the Hansalim Federation which ultimately come from their combined sales. The chart below, Figure 1.5, gives you an idea of the amount of interaction between consumers and producers in the course of a single year. It shows the number of ‘person-visits’ categorized by each Life Coop and by the type of activity in 2023. Exchange refers to activities involving interaction between producers and consumers and engagement refers to activities among consumers themselves. You can see that there were around 59,000 encounters between individuals in 2023 that were directly facilitated by Hansalim’s member Life Coops. Although many of these are repeat visits of individuals (so the total number of people involved will be somewhat less) you still get a sense of the sheer scale of relationship building that is going on within Hansalim.

In addition to selling to members and organizing member activities, Life Coops also engage with the wider community by running a whole range of educational activities and training, community kitchens, environmental campaigns and community building activities and some have also set up new cooperatives in solar power and in the care sector. On top of all these activities, the high point of Hansalim’s cultural life are the festivals which are held at national and local levels. For example, the Autumn festivals bring producers and consumers together for food, drinking and traditional games and dancing. They provide a special context for making friends and creating a sense of shared identity and camaraderie.

For consumers and producers then, there is a lot of fun to be had as a member of a Hansalim community. This is a vitally important part of the rhythm of hard work broken up by fantastic celebrations and informal contexts for relaxation together. None of this would be possible, however, without the hard and often hidden work of the Practitioners.

The special role of practitioners

In Hansalim, employees are referred to as ‘practitioners.’ They are the people who make it possible to put the producer-consumer relationship into practice by running the businesses, coordinating movement activities and organizing the many processes that are required to keep each member organization running and working together as a federation. They are not only professionals in logistics, marketing, strategy etc. but they also act as mediators between consumer and producer members and their organizations. Whereas a manager in a corporate enterprise might be able to focus solely on negotiating financial dealings with clients and suppliers, Hansalim practitioners often find themselves also negotiating the complex conflicts in values and expectations between Hansalim members, making their role especially difficult and important.

The largest employer of practitioners within Hansalim is the Business Federation which takes the next largest share of revenue after the Life Coops (8.86%) to cover the costs of labour, logistics, promotion and marketing, product development etc. One of the most important assets managed by the business federation is the Anseong Logistics Centre.

Finally, the smallest share of the margin (0.81%) is used to fund the Hansalim Federation which organizes the national-level governance and policy-making processes, supports Hansalim’s educational, cultural, publishing and research activities, coordinates collaboration and solidarity activities with others in Korea and especially small-scale farmers abroad, and provides support to the member Life Coops.

In 2023 there were a total of 291 practitioners working in the member Life Coops, a further 235 working for the Business Federation and 40 at the Hansalim Federation. These were supplemented by 1,396 Activists working in the stores and to organize member activities (see Figure 1.6 below). Together with the 3,579 producers and processors they generate enough revenue to support themselves and the broader collective efforts of the Hansalim Life Movement to bring about social and cultural change towards a more sustainable way of living.

A report by Hansalim in 2020 estimated that, across the whole of Hansalim:

“There are 489 practitioners, 1,544 activists, 238 executives, 337 others, and a total of 2,370 members nationwide who organise this vast membership into businesses and movements. Add to this the 2,192 primary producers and 1,241 processors, and you have 6,041 people (as of December 2019) supporting their families.”9

With such a large and complex organisation, you might think that there must be some strong central authority controlling everything from the top down and making sure efficiency is maximised and operations meticulously coordinated. Happily (or perhaps sadly, depending on your point of view) that is not the case in Hansalim.

1.5 Governed through deliberative democracy

One of the most extraordinary features of Hansalim is the depth of their commitment to deliberative democracy and local autonomy. This emphasis on democracy has deep roots, but before we explore those in more detail (see chapter 2) it is worth having an overview of how Hansalim fits together today as a federation of democratic organisations. The governance structure of Hansalim is based on the principles of subsidiarity, mutual responsibility and deliberation rather than top down command and control.

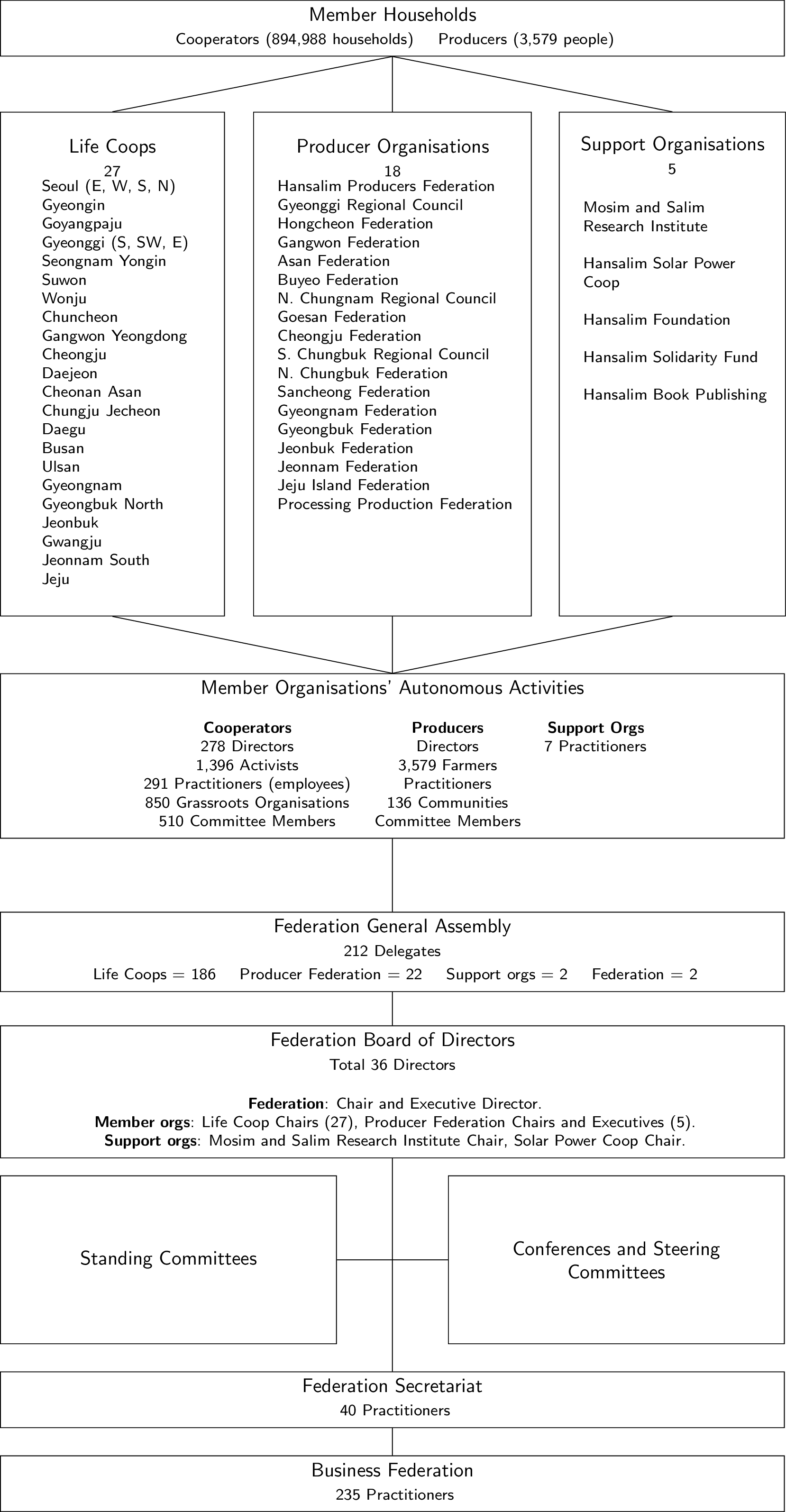

Subsidiarity

Below, Figure 1.6, is a diagram of Hansalim’s various organizations as they existed in 2023 and how they related to each other, laid out in order of how authority is delegated from top to bottom. At the top are the individual members. The 890,000 Member households and the 3,579 Producers. They are the owners of Hansalim. Below you can see the Life Coops, Producer Organizations and the Specialised Organizations and in the box labelled ‘Member Organisations Autonomous Activities’ I have listed the numbers of people involved (as far as data is available). The word ‘Practitioner’ here is Hansalim’s term for employed staff member (as mentioned above). Remember that ‘Activists’ refers to consumer members paid to either organise producer-consumer activities or work in the stores. Between them, the member organisations elect a total of 212 delegates to the General Assembly of the Hansalim Federation (1-year terms limited to two consecutive terms). The consumer organisations are allocated a total of 186 delegates (adjusted for each Life Coop according to the size of membership) and the producer organisations have 22 delegates between thim. The General Assembly elects a board of 36 directors including the chair of directors who holds the title of president (maximum of two consecutive 2-year terms). The board appoints the executive directors of the Federation, the Business Federation and the support organizations but cannot interfere with the governance and management of the member Life Coops or producer organizations. The standing committees, conferences and steering committees are where deliberations take place over policy and strategy decisions and they operate at local and national level involving producers, members and practitioners.

So you see that neither the Hansalim Federation nor the Business Federation are ‘apex’ organisations or ‘head offices’ but rather, they are supporting organisations whose purpose is to facilitate the successful business of the Life Coops and producer organisations while running the delegated shared movement activities and supporting the independent movement activities of member organisations.

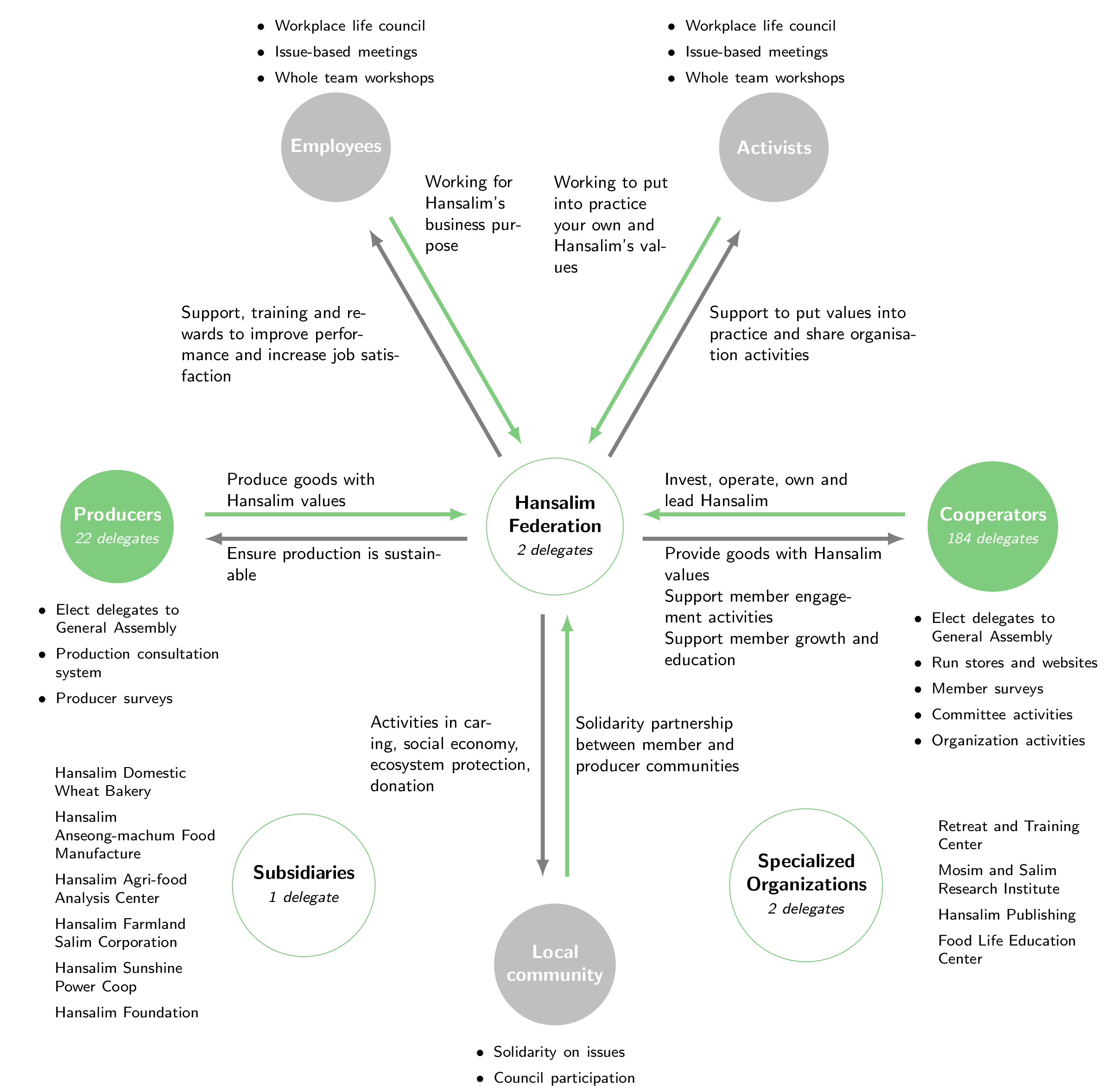

Mutual responsibilities

The way the Hansalim Federation sees itself in relation to the other Hansalim organisations can be understood with the help of the following diagram, Figure 1.7, which was published in the Hansalim 2017 White Paper.10 I have reproduced it here with some minor modifications and translated it into English. With the Hansalim Federation at the centre each of the stakeholders are listed along with their mutual responsibilities in relation to the Federation. Hansalim’s stakeholders include five categories: Producers, Members (i.e. consumer members), Practitioners, Activists and the Local Community.

Along with Producers, the Members share the main responsibility for governance of the federation and their local associations and Life Coops. Members elect delegates to the General Assembly, participate in committees, respond to and carry out member surveys and also govern the business and movement activities of their own Life Coops. Members are also expected to consume responsibly and encouraged to participate in activities to support producers and help the local community. From the Federation they receive goods produced according to Hansalim standards and values as well as support (organisational and financial) for member engagement activities and member education.

Producers also elect delegates to the General Assembly, participate in the production consultation system and respond to and carry out producer surveys. Their responsibility to the federation is to produce goods according to Hansalim standards and values and in return the federation is tasked with ensuring that their livelihoods are sustainable.

The Practitioners’ main responsibility is for running the business activities of the member organisations and the shared business organisations (i.e. the Business Federation) but they also play a role in supporting the governance and movement activities. Although Practitioners are not directly represented in the General Assembly, the executive directors (a Practitioner role) sit on the board of directors at each level of organisation from member to federation respectively. The Workplace life council is the closest thing to a labour union in its role of representing the interests of Practitioners. The Federation’s responsibility to Practitioners is to support their training and performance and increase job satisfaction. However, the role of Practitioners has evolved over time and is becoming increasingly ambiguous. Originally, during Hansalim’s early days, their main role was to act as a bridge between producers and consumers while running the business activities. In the beginning people joined Hansalim as Practitioners to support their shared vision and often worked very long hours for low pay doing whatever was needed. Now, as Hansalim has grown larger, many of those who worked for Hansalim from the early days have taken on managerial positions while the hiring of new employees has become more formalized and specialized. As a consequence, the role of Practitioners as a bridge between consumers and producers has become weaker and the emphasis has shifted towards running business operations.

Activists were originally member volunteers whose role was to organize consumer activities and also act as a bridge with producers. After a while, it was decided that they should be financially compensated for their work and their roles should be more clearly specified. Now, Activists are members who have received training for specific roles and are paid a wage to work in the stores, receive phone orders and organize various activities for producers and members.

The Local Community is included as a stakeholder category as producers, members and activists seek to identify and take action on local needs. They work with local community organizations and representatives of such organizations are also invited to participate on various councils as appropriate. In fact, it is quite common for Hansalim members and producers to simultaneously hold official positions in Hansalim and other local grassroots organizations and social enterprises.

The organizational role of the Hansalim Federation in this structure is to support each of these different stakeholders to realize their own and Hansalim’s values in their various activities. A large part of this involves organising committees and meetings, collecting opinions from members and supporting the deliberative process among member organisations through training, research and timely communication of information about each area of business and activism.

Deliberation

The deliberative processes in Hansalim encompass the grassroots groups and conferences and work their way through the various levels of organisation to the committees, boards of directors and general assemblies at local and national level. Formal meetings are required to follow the regulations in the articles of association and bylaws and are usually run according to an adapted set of rules from Robert’s Rules of Order by Henry Martyn Robert (1837-1923)11 and scrupulously minuted and reported. Opinions are also gathered through online forums, member surveys and organisation messaging boards. Finally, the auditing process provides an opportunity for independent monitoring and constructive criticism from people elected to the Supervisory Council.

At the heart of the deliberative process is the delegate system. In each Life Coop where the number of members is large enough to make direct participation impractical, delegates are elected with the responsibility of reflecting the opinions of the wider membership through their participation in the General Assembly. Their core role is to ‘ensure that the wishes of members are properly and responsibly represented’.12 Thus, in addition to attending the General Assembly to vote on decisions and elect directors, they are expected to be the channel of communication between the board of directors and members. To fulfil this role they need to join in with member activities and gatherings, listen to the opinions of other members, build relationships of trust and participate in the regular briefing sessions in preparation for the General Assembly. The term of office for delegates is set by the articles of association of each Life Coop within a range of four years. As members of the General Assembly they have the authority to amend the articles of association, elect and remove officers (i.e. members of the board of directors and executive directors), approve financial reports and budget plans, approve the supervisory council reports and decide on refunds of invested contributions to members who withdraw or are expelled.

This is quite a heavy responsibility for an unpaid position and the success of the deliberative process depends upon the voluntary commitment of members willing to take up responsibility for democratic management of the cooperative. It also looks like a very inefficient system of management which requires excessive amounts of time and resources for the sake of a very slow decision making process. As early as 1984, the Hansalim Moim were very familiar with the difficulties of democratic management. So much so that their training material for consumer cooperative leaders states: “Democracy is a good thing, but it’s a pain in the arse!”13

So how can we explain the persistence of Hansalim members with such a cumbersome system of governance? And does it bring any benefits that justify the continuing investment of time and energy? For an answer to the first question you will have to wait for chapters 3 which describes the historical roots of Hansalim in the pro-democracy struggle. For now, I want to offer an answer to the second question. What is the point of such an apparently inefficient system of management?

1.6 On a tilting unfinished journey

The answer is that the only way to hold together a movement of continuous collective action without resorting to coercion is through bringing conflict into the open where it can be transformed and resolved. Consider how difficult it is for a family to get along without arguments and disagreements. Even petty differences can cause lingering feuds. In a family as in a commerical company, such conflicts are typically resolved by whoever has the authority to pass judgement, dole out punishments and rewards or even expel the ‘trouble maker’. Now imagine a group of people who were not born or hired into a hierarchy of power relationships but got together voluntarily, expecting to be treated as equals. Unfortunately, the absence of a pre-existing power hierarchy does not automatically remove the thorn of conflict but simply submerges it within the informal network of personal relationships, where, hidden in the rich soil of privacy it germinates. Far from generating spontaneous harmony, this anarchic anti-hierarchical form of organisation multiplies conflicts exponentially.

The only way to counteract the undermining effects of the formation of cliques and factions around conflicting opinions and interests is to acknowledge the inevitability of their existence and provide a context for healthy confrontation. The purpose of democracy in Hansalim is to create that context. The point of doing so is that when conflicts are explored and resolved in public, the uncomfortable process of resolution itself generates a kind power that is totally inaccessible to a ‘strong leader’ who rules by right or might. It is the power to act in concert, to work together in a kind of messy unity that does not crush diversity but turns it into a source of creativity.

The term used by the poet Kim Ji-ha to describe the evolutionary nature of a living movement such as Hansalim is “tilted balance” or a kind of dynamic (dis)equilibrium:

“The philosophy of ‘tilted balance’, along with paradoxes, is crucial to understanding life. However, the term ‘tilted balance’ does not adequately describe the world of life. That is, the adjective ‘tilted’ and the noun ‘balance’, which denote states, do not capture the dynamism of the ever-changing world of life. The world of life is constantly tilting and tumbling rather than being in a stable balance.”14

Yoon, in his 2024 report about Hansalim’s evolving structure writes:

“When choosing policies and institutions in Hansalim, we can present the ‘tilted balance’ in the”Hansalim Manifesto” as a decision-making principle that balances reality and ideals, associations and businesses.”15

Hansalim’s journey from a small movement of producers and consumers to a national federation has been far from smooth and simple. As successful as it has been, it was and still is fraught with struggles, controversies, failures and frustrations. One common phrase I heard from my interviewees in Hansalim is that “Hansalim looks beautiful from far away, but when you get closer you can see it is a lot more ugly.”

That ugliness is the reality of trying to work and live together with people whose backgrounds, perspectives and desires are so often radically different and even competing. It is the challenge of finding compromises that reflect a shared core of values while also trading off some of those values against others for the sake of a unity which is always and inevitably unsatisfactory. That is why, in addition to “moderation” - the virtue required to find the “middle way” - “discernment” is also key to maintaining this continually oscillating ‘tilted balance.’ Again, Kim Ji-ha explains this idea as a key aspect of the Confucian concept of the doctrine of the mean (中庸):

“A more precise expression of this spirit is the term shijung (discernment - 时中), which appears in”The Doctrine of the Mean”, the second of the Four Books, written by Confucius’s grandson Zisi (子思). It means to strike a balance in an ever-changing situation. This kind of person is called a virtuous person. A person who is principled, but is also able to make judgements and adjust their behaviour according to the time and situation.”16

It is this principle, rather than any specific organisational model, that appears to define Hansalim’s journey and their continuing commitment to deliberative democracy. It provides the means for collective discernment as a process of mutual understanding through talking and listening.

1.7 Conclusion

For those in Europe and other regions of the world outside Korea, Hansalim can appear to be a uniquely Korean phenomenon. “Surely, it is only the collectivist culture of Korea that makes such a community possible. It could never succeed in our hyper-individualist western societies.” But you must not forget that the two strongest influences on contemporary Korean culture are Confucianism and American consumerism. The former provided the rationale for a strictly hierarchical and patriarchal culture that dominated Korean society for several hundred years before the latter collided head on with it during the post-war period, giving rise to a uniquely oppressive mixture of competitive consumerism and rigid conformism.

It was in this context that Hansalim emerged as a concrete expression of the desire felt among many at the time for a different kind of society built upon equality, mutual respect and care for other humans and the nonhuman world. I have a feeling that this same desire has not gone away, but only deepened, not only among Koreans but equally among contemporary people in Europe and beyond.

However, no matter how much you desire to create something like Hansalim, managing such a large organization (or rather, federation of organisations) without a dictatorial head office but in a deliberative and democratic way is very, very hard work. If you were in it for the money, you would not do it like this. But for every member of Hansalim I have spoken to so far, its not about money, but about being part of a community dedicated to caring for each other and to creating a peaceful and thriving future for the world. So as a reader from outside Korea who aspires to transform food systems, you need to keep in mind that Hansalim’s success is mingled with failures and disappointments and comes at the cost of a great deal of personal sacrifice, collective conflict and agonising, trial and error and lots and lots and lots of ….. meetings. Just look again at Figure 1.6 and notice the number of committee members in the column for Life Coops!

Having said all that, even if you are prepared for such a challenge, I do not think it is possible to simply transplant Hansalim’s model to other countries. It has its own history and unique context from which it emerged and it is not a static model but an evolving community in a continual process of change.

But what is perhaps much more useful than a blueprint, is Hansalim’s story and the myriad stories of the people who practice Hansalim (as a verb). These stories carry the values of Hansalim, the spirit and emotion of Hansalim people and the experience of countless challenges and success that they faced along the way. These stories, more than anything else, carry the seeds that could produce new fruit in other contexts, as long as there are those with the determination to cultivate them.

To hear some of these stories, I am afraid you will have to wait a little longer for the rest of the book to be written and published. I’ll do my best to finish it as soon as possible! Each new chapter will be published here as soon as it is written.

And of course, it is a story without an ending. Which means, in all likelihood, there are those among you reading this book who will end up playing a role in it one way or another.

https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20230524000525↩︎

Kyung Moon Hwang, A History of Korea, 3rd Edition (London, England: Red Globe Press, 2021).↩︎

Hansalim, “Because of You We Live: Hansalim 30th Anniversary White Paper,” research report (Seoul, Korea: Hansalim; Hansalim, 2017).↩︎

Hansalim, “Hansalim Federation 14th General Assembly Resource Book,” research report (Seoul, Korea: Hansalim Cooperative Federation; Hansalim, 2024).↩︎

Hansalim, “Hansalim Annual Report 2021,” research report (Seoul, Korea: Hansalim; Hansalim, 2021).↩︎

Hansalim, Hansalim Manifesto (English Version) (Mosim; Salim Research Institute, 2021).↩︎

Hansalim, “Hansalim Federation 14th General Assembly Resource Book”.↩︎

Hansalim, Hansalim Meetings Protocol, version 2020.6 (Mosim; Salim Research Institute, 2020).↩︎

Hansalim, “The Meaning and Role of Hansalim’s Delegates,” technical report (Report of the Policy Planning Committee, 2018).↩︎

Wonju Catholic Diocese, “The Cooperative Movement: For the Democratic Operation of the Cooperative” (Catholic Diocese of Wonju, Office of Social Services, Department of Social Development, 1984).↩︎

Kim Ji-ha, ‘On the Tilted Balance,’ The Complete Works of Kim Ji-ha, Volume 2, Practical Literature, 2002. Reproduced in: Yoon, Hyunggeun, ed. 2004. Salim’s Words. Mosim and Salim, Book 3. Seoul: Mosim and Salim Research Institute. p. 184-185. (Translation: J Dolley).↩︎

Hyeong-Geun Yoon, “History of the Evolution of the Hansalim Composite Organisation,” research report, Research Report (Seoul, Korea: Mosim; Salim Research Institute; Hansalim, 2024), translation by J. Dolley.↩︎

Kim Ji-ha, ‘On the Tilted Balance,’ The Complete Works of Kim Ji-ha, Volume 2, Practical Literature, 2002. Reproduced in: Yoon, Hyunggeun, ed. 2004. Salim’s Words. Mosim and Salim, Book 3. Seoul: Mosim and Salim Research Institute. p. 182. (Translation: J Dolley).↩︎